How Can I Bring an Administrative, Human Rights or Constitutional Challenge?

Administrative law, human rights and constitutional law fall under an umbrella called public law. Public law regulates the relationship between the State and individuals.

It defines what rights (i.e. the things people are entitled to) individuals have before agencies and government departments and what obligations (i.e. the things people have a duty to do) these public bodies have towards individuals.

It determines the competence of authorities (i.e. what they can and cannot do); and

It indicates which remedies an individual can get for the violation of her or his rights.

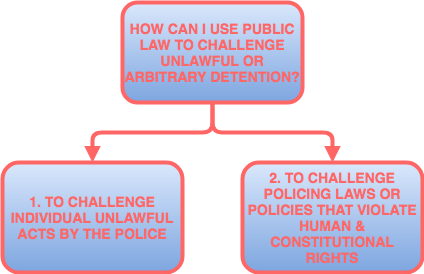

This applies to the actions of the police, who are agents of the state who work within public authorities (i.e. the police service). For that reason, it is often possible to challenge unlawful or arbitrary arrests on public law grounds.

This is different to a civil claim that are more individual and compensation focused. In public law challenges, the focus is on the unlawfulness of the policies or actions of public bodies, rather than the harm to the individual.

This type of legal action could be used in two different ways:

Focus Point: How do the two types of challenges interlink?

It is often possible and necessary to combine these arguments in your case.

For example, take a case where may challenge an individual detention. You may first challenge the detention for breaching the law on criminal procedure (i.e. “ultra vires” – see below).

However, if a court rules that the detention was lawful, your remaining option is to challenge the law on detention itself by arguing they are unconstitutional or violate your human rights.

Is a Public Law Challenge Right for Me?

Before you bring a public law claim, consider the following advantages and disadvantages:

| ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

|---|---|

| You may be able to get a remedy to compensate you for your loss or harm. | When responding to a complaint, the officer involved may make allegations about your own behaviour in order to justify their actions, which can be upsetting. |

| Making a complaint makes your concerns official, and a record will be made of those concerns and kept by the police force. | Unless you can access legal aid or get financial support, bringing claims can be expensive. |

| Public law challenges can led to law and policy reform. | Public law claims can be very time consuming and you will be responsible for gathering your own evidence. |

| Your complaint might help other people making complaints against the same officer to show a pattern of abuse or misconduct. | Levels of compensation awarded in public law challenges are often much lower than in civil claims. |

| Courts are in principle independent and less likely to be biased towards the police. | |

| Litigation can create awareness around an issue. |

What Laws Can I Enforce?

If you are making a public law challenge, in many systems your claim must be based on a «ground» or “cause of action”. The specific grounds or causes of action available will depend on your country’s legal system but we outline some common and relevant grounds below:

(a) Habeas Corpus and the Principle of Ultra Vires

Habeas corpus is a legal principle that gives someone the right to be brought before a court and seek their release from detention if it is found to be unlawful. In other systems there is a principle called “ultra vires” that operates in a similar way so that a detention will be ultra vires if it is made outside the national laws and procedures relating to detention.

- For more information on the laws that could ground a habeas corpus/ultra vires claim, see the sub-sections on the legal framework relating to the issue in your case.

Example: Article 99, The Constitution of Pakistan

This provides courts in Pakistan with the power to issue a writ of habeas corpus to demand that people unlawfully held in detention can be released. The Pakistani Supreme Court has exercised this power in many cases, including:

- Government of West Pakistan v. Begum Agha Abdul Karim Shorish Kashmiri

- Muhammad Azam Malik v. A.C. Karachi

(b) Human or Constitutional Rights

A law, policy, regulation or action of a public authority could be challenged if it violates a human right protected in your national law or constitution, such as the right to liberty.

(c) The Principles of Irrationality and Proportionality

Even if there are no specific laws governing aspects of detention, detention could be unlawful if it is irrational or disproportionate. The test here is to consider whether the decision to initially or continue to detain you was «so unreasonable that no reasonable authority could ever have come to it«. This is a high threshold to meet but it could apply where public authorities act completely incompetently.

Who Can Bring a Claim?

In order to bring a public law challenge, you must have «standing«.

- This generally requires that you are affected by the act of the public authority defendant. This includes anyone who has been detained.

- It is also possible in many countries for civil society organisations who has an interest in that area to take legal action in the public interest.

For more information, see Who Can Take Legal Action? on the A4J Going to Court: Q&A.

Who Can the Claim Be Brought against?

Public law claims can generally only be brought against public bodies. Examples of potentially relevant public bodies include the police force, the relevant government ministry or the State as a whole.

Example: Republic v Speaker of the Senate & another Ex parte Afrison Export Import Limited & another (Kenya)

In this case, the court ruled that it has the power to review the work of the senate and any other organ of government. This is particularly important where laws created by the senate are being challenged.

What do I Need to Prove?

In public law actions, it’s the claimant who has the “burden of proof”. This means the person bringing a public law claim needs to prove their case.

- You need to have a set of facts that describes what happened and evidence that supports your “version of events” (i.e. what you are saying happened).

- In many countries, you have to prove your case to a standard of proof known as the balance of probabilities (i.e. you need to prove that there is more than a 50% chance what you are saying happened).

For tips on what evidence might be useful, see the evidence sub-section in the section on the issue that your case relates to.

When you have gathered evidence, your version of events and the evidence that supports it will need to be presented to the court. Usually, this will be presented in written “pleadings” or submissions that forms the basis of your civil claim (see below).

What information should I include in my claim?

In your written claim, you should generally:

- Describe the detention and the circumstances surrounding the detention.

- Identify relevant police officers or departments and explain their roles.

- Explain what happened in any hearings in court.

- The date, time and place of the arrest, the charge and any hearings.

- Identify the legal basis of your claim (i.e. what law are you arguing has been breached? What is your ground or cause of action?)

- State the reasons why you consider the detention was unlawful or arbitrary.

- Outline the evidence that supports your reasons (see below).

- Explain the consequences of the detention, and the reasons why it has caused you or other people loss.

- Explain what remedy or outcome you want.

You must gather evidence that will be accepted in court (this is called “admissible evidence”).

- You can generally only submit evidence to the court which is ‘relevant’. Relevant evidence is that which relates to essential facts that you must prove to succeed in your case and which is not admitted by the other party.

- The precise facts of each case and the exact rules governing the evidence will vary according to the country in which you are bringing your claim.

I’m challenging a systemic issue. What evidence do I need?

If you are challenging a systemic issue, such as an unfair law or practice, you will need evidence that is broader than a single detention.

Generally, you will need to show the scale of the problem you are challenging. The following types of evidence may therefore be useful:

- Evidence of the impact of a given law/practice (e.g. statistics on how a certain group is disproportionately targeted by detentions);

- Evidence of how there is insufficient safeguards or how safeguards are routinely not enforced (e.g. statistics on the number of people detained without charge or for long periods of time)

- Comparisons with international standards and laws in other countries to highlight a lack of safeguards.

You may be able to find this information in reports by NGOs, reports from UN human rights bodies on the situation in your country, national police statistics or reports of government bodies.

What Procedural Steps do I Need to Take?

The exact procedure you will follow will depend upon the type of claim, the court, the procedural rules of the court and the jurisdiction in which you are bringing the claim.

In many countries, the process of enforcing public laws against public bodies is called “judicial review”.

Example: South Africa

Judicial Review has been used many times since in South Africa since the establishment of its recent constitutional democracy and has been a relatively effective means for holding public bodies accountable. The South African Constitutional Court is able to use this process to review procedural and substantive issues.

While in many Latin American countries, a process called “amparo proceedings” are used to challenge unlawful acts by public bodies.

Focus Point: Amparo Proceedings

In some Latin American countries, the amparo trial is one of the most efficient ways to defend oneself from abusive government acts and when constitutional rights are violated.

- The amparo trial can be invoked by any person to whom his or her rights have been violated.

- Amparo trial and its procedural venue can vary according to the procedural law of each country.

The following steps are common in many systems:

Public Law Procedure

-

1

Notify the defendant

Write a formal letter to the proposed defendant setting out the proposed claim and what you wish to achieve. A response is usually requested from the defendant.

-

2

File your claim form

Submit your "claim form" to court within the required "time period" (there is usually a number of months of years after the incident within which you must file your claim).

-

3

Present your statement of claim

Present your grounds for the claim to the court, which will be shared with the defendants. This document can be referred to as a "statement of claim", "statement of case", "particulars of claim" and "complaint". This then have to be shared with or "served" on the defendant.

-

4

The permission phase

In some countries, you have to apply for permission to bring a public law claim. This is a process where your claim is vetted to see if it's credible or has reasonable prospects of success before the defendant has to respond. The defendant can present arguments at this stage. In other countries, the claimant does not have to apply for permission but the defendant can make an application to dismiss the case or apply for summary judgment. The court will then decide whether the case is sufficiently credible or has reasonable prospects of success in order to decide whether to allow it to continue.

-

5

The defence

Defendants will then have a chance to explain their position. They can either accept all or part of your claim, or deny your version of events in full. This document is known as the "defence".

-

6

Disclosure or exchange of evidence

You and the defendant may be asked to share the evidence you are relying with each other. If you are using witnesses, you will usually need to include what they are going to say in a "witness statement" or "affidavit".

-

7

Notification of a hearing date

-

8

The Hearing

At the hearing, you will present your arguments, including a review of the key evidence already likely filed with the court, witnesses may give oral evidence and can be questioned by the lawyers. The court then makes its decision.

-

9

Appeal

The losing party generally will have the right to appeal this judgement before a higher court.

What Happens if I Win?

Generally, the following remedies can be awarded in public law challenges:

- Writ of habeas corpus – this means that the detention is invalidated, and you would be released;

- Injunction – this can oblige the state to do or stop do something (e.g. release you from detention);

- Compensation – you may be financially rewarded to compensate for your loss or suffering; or

- Striking down of law or policy – in countries with a strong constitutional mandate, the law itself can be ruled unlawful.

Can I Take My Case to a Regional or International Human Rights Body?

If your claim is based on human rights and you lose at the national level, it may be possible to bring your case to a regional or international human rights body. Bringing a claim to a regional or international court could be helpful in the following cases:

- You have tried and failed to bring a public claim in national courts (up to the highest level);

- The national courts in your country are ineffective;

- The judgment from a national court hasn’t been enforced or followed by the government.

Individual complaints to these bodies are like bringing human or constitutional rights claims before national courts (they are legal complaints) so the earlier guidance in this section applies.

(a) Regional Human Rights Commissions and Courts

Regional human rights courts and commissions can enforce regional human rights treaties when available domestic mechanisms (courts or other) have failed to protect your human rights. These bodies can launch investigations into your case, facilitate negotiations between you and the government, declare that your government has violated your human rights, and order the government to give you a remedy and change its laws or policies.

Examples of Regional Human Rights Courts

The main regional human rights courts are:

- If in Europe, you could go to the European Court of Human Rights which enforces the European Convention on Human Rights;

- If in the Americas, you could go to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights or the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to enforce your rights under the American Convention on Human Rights;

- If in Africa, you could go to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights or the African Court of Human and Peoples’ Rights to enforce your rights under the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights; and

- If in West Africa, you could enforce the same rights before the ECOWAS Community Court of Justice.

You may have the option of bringing an “individual complaint” (i.e. a case) to a regional or international human rights body if:

- Your case is being brought against the government

- Your case is based on human or constitutional rights

- Your country has signed and ratified a regional human rights treaty which gives a regional human rights court or commission jurisdiction to hear human rights complaints regarding your country.

- Your claim is considered admissible by the regional human rights court or commission. For your claim to be admissible, you generally have to show:

- That you are a “victim”of your government’s actions or omissions (i.e. that you were arrested). This is similar to proving “standing” in national courts.

- That you have some evidence to back up your claim.

- That you have first tried to bring your claim before national courts – this is often referred to as the “exhaustion of local remedies” (the exception to this rule is the ECOWAS Community Court of Justice).

There are many cases where regional human rights commissions and courts have been able to secure justice for people subject to arbitrary detention.

Example: Abdel Hadi & Others v Sudan (African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights)

The claimants were displaced persons whose refugee camp was raided by police who rounded up and arrested the people in the camp. None of the claimants were informed of the reason for their arrest, were granted a lawyer and they were held without charge for 12 months.

The ACmHPR held that this amounted to a clear violation of the right to liberty and security in the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and ordered compensation, an investigation into the arrests and necessary amendments to Sudanese law.

Example: Case of Gangaram Panday v. Suriname (Inter-American Court of Human Rights)

The family of a person who died in military custody at an airport brought a claim against the State for violating the deceased’s right to liberty, and other rights. The IACtHR held that the failure to present reasons for the detention or a charge amounted to an arbitrary detention and a violation of the right to liberty.

(b) Individual Complaints to UN Human Rights Treaty Bodies

There may be the possibility to enforce your state’s human rights obligations through individual complaints before UN human rights treaty bodies. This could be particularly useful if you are based in a country that is not covered by a regional human rights court.

While these aren’t courts, they have individual complaints mechanisms which hear individual complaints like a court. In a number of cases, they have made recommendations to governments to release people from arbitrary detention and pay compensation.

Example: Fillastre v Bolivia (UN Human Rights Committee)

Fillastre was charged in 1987 for offences punishable by imprisonment of one to five years. His proceedings were delayed, partly due to the judge’s desire to gather further evidence, and he was expected to be tried in 1991.

First, the UNHRC held that “what constitutes ‘reasonable time’ is a matter of assessment for each particular case”. However, they held that “evidence-gathering” did not justify a pre-trial detention of four years so there was a violation of article 9(3) of the ICCPR («anyone arrested or detained on a criminal charge shall be entitled to trial within a reasonable time»).

To access these bodies, your country must:

(i) Be a party to the relevant international human rights treaty

AND

(ii) Have accepted the competence of the treaty body to receive complaints against the state; this may be in the optional protocol to the treaty

Key Resource: OHCHR Website

Here you can find information on:

- What countries have signed and ratified different human rights treaties;

- The different treaty bodies that exist;

- Guides for how to submit a complaint; and

- Past cases and examples