Equality within marriage

What is equality within marriage?

Historically, marriage was often rooted in the idea that a woman was to obey her husband. Married women very often have fewer rights than men and in some cases, married women’s rights are also inferior to unmarried women.

There is, however, ongoing progress in changing such laws.

A 2000 reform of Ethiopia’s Family Code eliminated a husband’s ability to stop his wife from working.

Equality within marriage refers to women having the same rights as their husbands and the same capacity to make decisions whilst married and not having the husband control the decisions a wife can make.

Reduced capacity of the wife and control from the husband over women’s engagement in economic activity and important decisions. What can you do?

In some countries, a married woman’s capacity or ability to make decisions is reduced by law and she is required to have her husband’s permission or authorisation for various things, including entering into contracts; opening a bank account; applying for jobs; and buying or selling property.

This severely restricts a woman’s autonomy and ability to participate in the economy as an independent citizen. This means that even in cases where she is in an abusive or unhappy relationship, a woman may have no choice but to stay with her husband.

In 37 countries, including Botswana, Pakistan, and Myanmar, women need their husband’s permission to apply for a passport, and in 18 countries, women cannot apply for a job without their husbands permission.In Chile, women married under the matrimonial regime of “Conjugal Society” are subject to a more restrictive regime than if not married or married under a different regime. Under the Conjugal Society regime, the wife is unable to administer her own and common property, and the husband is the party that by law is in charge of administration of common property and must carry out transactions of the wife’s own property for her and with her authorisation.

Such discriminatory restrictions violate equality before the law, and various economic and social rights such as property rights, the right to work, or the right to social security which are in the constitutions of most countries.

The sections below will highlight different routes to protecting your rights depending on what you are seeking.

Your husband is refusing to give his authorisation. You are seeking to replace your husband’s permission for your particular case.

Civil Remedies provided for in the law:

Laws and policies which provide for unequal rights within marriage often themselves provide for a procedure that applies if a woman’s husband refuses to provide authorisation. This may involve applying to a civil court for a judge to provide authorisation instead of the husband.

Civil claims solve disputes between private parties, such as two individuals, a couple, two companies or an individual and a company. The purpose of civil claims is for a judge to give you relief or a remedy, that is, a solution to your individual problem with the other party. This can be:

-compensation or money in the case that you suffered harm

-it can also be an order from the judge to do or not do something

-it can also be an order from the judge allowing you to benefit from certain rights. For example, to divide a property in your favour, administer an estate or decide that you are entitled to certain rights.

In this case you would ask the judge to provide authorisation instead of the husband.

Claim: Civil claim in a civil court

By whom: the wife

Against: the husband

Asking for: to replace the husband’s authorisation to allow the wife to carry out specific activities.

Step 1: Think about why your husband is not giving you authorisation. Is he missing? Have you lost contact with him? Is he being unreasonable? Start gathering evidence that your husband is being unreasonable or unable to give authorisation (for example, if he is missing).

Step 2: Look at where the required authorisation is regulated – for example, in a civil code, or specific legislation related to banking, employment, insurance etc. There is often a provision which allows a judge to provide authorisation if a husband is unreasonably unwilling or unable to do it.

For example, Article 138 of the Chilean Civil code allows a woman to seek authorisation from a judge if she wants to enter into contracts over joint property in the case that the husband is unable to do so due to a long term impediment, absence or disappearance and if it causes damage to the wife.

Article 138 bis of the same code allows a woman to seek authorization from a judge if she wants to enter into contracts over her own property that is usually administered by the husband, in the case that the husband declines to give authorisation with no justification.

Step 3: Seek legal advice on the viability of your case and to take your case to court.

Proceedings will often involve:

- Going to a civil court.

- Provide evidence in support of the application for the judge to give authorisation instead of the husband. For example, evidence that the husband is being unreasonable or unable to give authorisation (for example, he is missing)

- An opportunity for the other party to object and offer evidence against your claim.

- The judge making a court order replacing the authority of the husband.

- Possibility of an appeal

This route is a good option for a case in which the focus is on solving the individual problem, but note that it does not address the systemic issue of the existence of the discriminatory law, and does not apply for future situations.

Public law challenges against unequal rights between men and women during marriage:

In many cases, it is either public policy or the law that discriminate against married women, defining them as lacking capacity, systematically propagating discriminatory policy. This kind of systemic issue that is best addressed through a constitutional or public law challenge.

A public law challenge allows you to contest a law, policy or a decision that denies legal protections to women, on the basis that these laws, policies or acts go against your fundamental or constitutional rights.

How? The process for such a challenge varies between countries – it may be, among other things, called a “constitutional petition”, or “amparo proceedings”.

For this to work, there must be a right on your constitution or other important law which lays out your fundamental rights that protects you. Most constitutions include a general provision of equality before the law or non-discrimination. Some countries have constitutional provisions specifically referring to equality in marriage – for example, article 31 of the Constitution of Uganda. Some countries may have other laws which refer to equality in marriage, which can be used to challenge unequal treatment of men and women in marriage which violates such protections.

Claim: Public law or constitutional claim in a constitutional court. Some countries allow you to go to a civil court.

By whom: the wife (can be supported by civil society organisations) and some countries allow civil societies to represent the public interest and take a case alone.

Against: in most countries, you can challenge an act by a public authority which gives the wife less rights than the husband. In some countries like in Peru (article 200 of the Constitution), laws are challenged through “unconstitutionality actions”. In some countries, acts by individuals or private institutions can also be challenged by a constitutional claim.

Asking for: declare the act or law unconstitutional and have it not applied in your case and in some cases it does not apply to the cases of other women.

How? The process for such a challenge varies between countries – it may be, among other things, called a “constitutional petition”, or “amparo proceedings”.

Proceedings will require:

-Finding a person who has had their fundamental rights affected: This would be the wife which is affected by the restrictions of inequality within marriage.

-Establishing which of your fundamental rights were affected: the right to equality and/or non-discrimination contained in most constitutions or other national laws can be effective but it could also be that other rights protected by the constitution are affected, such as your property rights, right to work, or others.

TIP: Depending on each country, the right to non-discrimination may only apply in relation to the enjoyment of other fundamental rights, rather than as a standalone right.

For example, in the UK, the Human Rights Act requires that discrimination has affected the enjoyment of one or more of the other rights in the Act.

Other countries, like Peru, allow for the right to non-discrimination to be protected as a standalone right.

-Getting legal advice on the likelihood of an amparo proceeding for your specific case.

-Initiate legal proceedings showing which rights were affected, how those rights were affected and why it is unconstitutional. You will need to provide evidence.

-The other party, the public authority or the Estate will also get a change to argue and give evidence against your claim.

-If successful, the constitutional courts may provide for an act, law, or policy to be declared unconstitutional. This often means that the act, law, policy cannot be implemented in an individual case (concrete application), but it may in some countries also have the benefit of not being applicable in ANY case (general application).

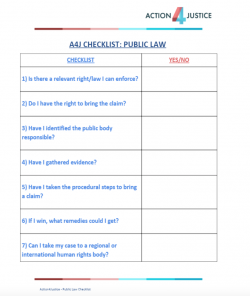

The following checklist may be useful when thinking of a constitutional claim:

Nombuyiselo Sihlongonyane v. Mholi Joseph Sihlongonyane, (470/2013A) [2013]. A case of general application.

In this case, Mrs. Sihlongonyane wanted to sue her husband over some marital joint property. She took the case to a civil court to get the administration of the common property, where the husband argued that a wife did not have the capacity to start legal proceedings because it was the husband who had to authorise her to do so. The judge in this case raised the question of whether this was constitutional to the High Court to decide.

Following the steps on the checklist above, Mrs. Sihlongoyane and her lawyers argued that:

1) She found a relevant enforceable law which was Section 20 of the constitution of Swaziland, which gives equal rights to women.

2) found that theyt had the right ask the high court to decide this constitutional issue under Section 151 (2) of the Constitution which empowers the High Court to generally, ‘hear and determine any matter of a Constitutional nature’.

3) the public body or law responsible was the common law” marital power” doctrine, which provided that a woman was not able to institute legal proceedings without the assistance of her husband and which was affecting her concrete rights.

4) & 5) They gathered evidence and took the procedural steps to make the complaint, which required the wife to be in a court proceeding and to have the constitutional request be part of that proceeding to solve her individual case, rather than a general one.

6) The remedy was that the Swaziland High Court held that the marital regime was invalid on the basis that it was inconsistent with sections of the Swaziland Constitution. This meant that Sihlongonyane was granted standing to sue her husband and applied that order of invalidity to all other women in similar situations.

Kirchberg v Fenstra, 450 U.S. 455 (1981) A case of concrete application

In this case Joan Feenstra’s husband signed a promissory note for $3,000 to pay for a service. He mortgaged his and Joan’s joint property as security without asking Joan. A Louisiana Statute known as the Head-And-Master law allowed the mortgage to be obtained without informing Joan.

The $3,000 note was not paid which lead to the person who was owed the money to obtain an order from a court to seize and sell their joint property and to ask a civil court (the Federal District Court) to assert that he was not required by law to inform Joan of the mortgage.

Following the checklist above:

Points 1, 2 and 3 of the checklists: Joan argued that the relevant law, the Louisiana law, went against the American Constitution.

Point 4: She presented relevant evidence to show that she had not given consent over the mortgage and presented a legal argument of how the law affected the Equal Protection Clause of the American Constitution and because of that she should not be responsible to pay a mortgage entered into by her husband without her consent.

Point 5: Joan’s attempt was rejected, and she appealed to the Supreme court

Point 6: The Supreme Court found that:

- the mortgage was void- Joan got her individual requests, but also that

- the Head and Master law was gender-based discrimination which was protected by the US Equal Protection Clause of the US Constitution. and was unconstitutional.

Thanks to this judgement, a few years later the state of Louisiana revised the relevant provisions (art. 2404) to grant equal administration for joint property for spouses.

A constitutional challenge is often a good route to challenge a law or policy which itself affects more than one individual, as it can be replicated by others.

Non-discrimination laws as a way to challenge discriminatory attitudes towards married women

It may be that the law is not the problem, but that an incorrect belief that the wife is less of an equal or under the control of the husband may persist among authorities, for example in local policy, or among the policy of private institutions like banks, private health providers and insurance companies in practice. This may lead to acts of discrimination. These acts can also be challenged, including through:

- An internal complaint procedure of the public body or private institution. It may be a good to use constitutional provisions or other laws in the complaint as a way of highlighting that they are incurring in unlawful discriminatory activity.

- Check if your country has an anti-discrimination law which allows a judge to order that policy or act by a private body to be reverted. These kinds of laws sometimes give fines to those that are found to have discriminated and compensation to those affected.

Claim: Discrimination claim in a civil court

By whom: the discriminated wife

Against: the public or private authority who discriminated against her

Asking for: Revert act by public or private authority and a fine/compensation.

Steps for this measure include:

- Collecting evidence on how you were discriminated against. This includes, for example, letters by the private or public authority saying that your husband’s consent is required to access a service, or to enter a contract, witnesses and even a copy of a company policy that is discriminatory.

- Seeking legal advice on the viability of your case and to take your case to court.

- Proceedings will vary in each country, but often involve going to a civil court, presenting your arguments, and providing evidence in support of the application. The other party will also get a chance to expose their arguments and give evidence against your version of events.

Bear in mind that often these laws require discrimination to have not just discriminated a person, but also affected any other fundamental rights, which can for example be the affected person´s property rights, or the right to access justice.

For more information on discrimination, see our discrimination guide.

Domestic violence and violence against women during marriage

If Domestic Violence or any other form of violence against women is taking place in your marriage, you can take legal action and seek support. For more information, please see our Violence Against Women guide.

Reproductive rights during marriage

If your reproductive rights are being affected during marriage, you can take legal action and seek support. For more information, please see our Reproductive Rights.

International/ regional challenges

International human rights treaties and conventions also protect the right to equal treatment of women within marriage.

What are my rights in international law

Article 23(4) of the ICCPR provides that states shall ensure equality of rights and responsibilities of spouses in relation to marriage and its dissolution.

Article 15 of CEDAW requires States parties to take positive steps to ensure women full equality in civil law. States must therefore repeal or amend any laws or instruments which have the effect of restricting women’s legal capacity.

Article 16 of CEDAW provides that states shall take measures to eliminate discrimination against women in all matters relating to marriage and family relations. This includes, in particular to equal marriage:

- The same rights and responsibilities during marriage and its dissolution.

- The same personal rights as husband and wife, including choosing a family name and profession.

- The same rights for both spouses in respect of ownership and management of property.

- Article 6 of the Protocol to the African Charter on the Rights of Women in Africa states that States Parties are obliged to ensure that men and women enjoy equal rights and are regarded as equal partners in marriage and that a woman shall have the right to acquire her own property and to administer and manage it freely.

TIP 1: You can find a detailed table of international law on marriage here.

TIP 2: You can click on this link and look for your country on the list. If your country is party to a treaty it must comply with the rights and obligations included in them. Your country may have applied reservations (limitations to the application of the treaty) when they became party to a treaty which you can also read.

TIP 3: You can search for cases in your country or in your regional system and see which rights have been most effective to uphold equal marriage rights in the past.

How to use these international law provisions in practice?

These provisions are especially useful for organisations and the community to hold their governments progressively to account particularly towards systemic change.

For more information on how to take your case to an international or regional body, please see the section on this guide “International Mechanisms to protect your rights”.