National Laws for Protection of Forests

This section concerns the National Laws that can be used to defend forests. These claims involve bringing governments to court to demand they comply with national laws governing the use and protection of forests. These claims can also be taken to hold governments and other relevant defendants (i.e. private companies) to account for their obligations to comply with national laws and to respect constitutional rights, human rights and Indigenous Peoples’ (‘IP’) rights. These claims involve bringing a government to court to demand they uphold their legal obligations to regulate and protect forests.

Claims under national law are typically brought against governments of countries who have either significantly contributed to deforestation or have failed in their legal obligations to protect and sustainably manage their forest cover.

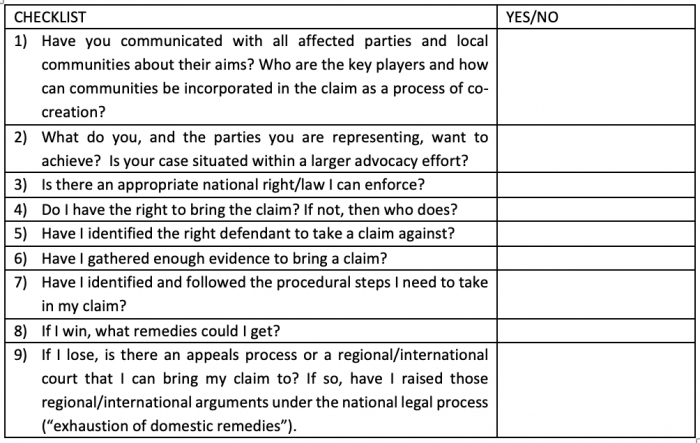

Consider the following checklist if you are thinking about making a forests defence claim based on your country’s national legal obligations:

If you are bringing a claim based on national laws for protection of forests, you will usually bring a claim under national laws and codes specific to forests and protected areas or under constitutional or national human rights law. These types of laws fall within an area of law called “public law” or “administrative law.” This is the body of law that regulates the relationship between State and individuals and are often brought against the government or public bodies. There are many different areas of public law. Each area prevents public bodies from doing certain things or requires them to do certain things, and provides consequences when laws are broken.

Once you have outlined the facts of your case, look at the areas of law below and see which most closely relates to your situation. Then check your national law to see what the law is in your country.

Remember:

Your legal analysis has to be supported by the evidence you have gathered. You may wish to seek legal advice. A lawyer with expertise in the relevant area should be able to provide advice on the options available to you and advise on your chances of success.The types of evidence you may need to support your argument will be outlined later in this section.

The specific content of these laws will change in different countries. However, below are the main types of law on which you could have a “cause of action” to base a national legal claim on.

What Laws Could I Base My Claim On?

A. Laws and Codes Specific to Forests/Protected Areas

In many countries, there are forest laws and codes specific to forests or similar protected areas that the government and other entities must follow. You may be able to bring a claim if your government, or another public body, fails to follow these laws. However, the exact content and cause of action will depend on your country’s laws, codes and regulations, and there may be circumstances where the defendants can be private companies. Therefore, remember to check the laws in your country before bringing a claim.

Case Example: Sanga v Teika

The claimants brought this timber rights case under the Soloman Island’s Forest Resources and Timber Utilisation Act. They requested an interim order to restrain the defendants from a number of activities including logging, building roads, and removing felled trees from the Tehakamagoku Land.

The Court granted the interim order, noting that continued logging would cause severe damage to the natural forest, as well as landscape and streams, and would take generations for it to recover.

This Guide primarily deals with laws that relate to deforestation, forest degradation and the need to protect forests from harm. However, forestry laws do not always need to wholly or directly relate to deforestation. Many countries have laws and codes that set out a number of other legal duties in relation to forests, including:

- Reforestation and conservation duties;

- Forest management duties; and

- Forestry reporting laws.

Case Example: Law 20,283 on Native Forest Recovery and Forestry Development (Chile)

This law governs the protection and recovery of native forests. It also regulates management plans for logging these forests.

TIP: It is not only laws about forests that can be relied on to protect forests. So many countries have general laws in relation to the environment and its protection which includes forests. Most countries also have laws regulating activities which may cause damage to forest areas, such as mining. These types of laws are discussed in more detail in Sub-Pages 7 and 8 of this Guide.

Key Resource: ClientEarth Forest Logbook

ClientEarth has created an excellent, open-access resource which is a centralised collection of a wide range of countries’ forest protection laws and governance. It also includes information on measures that impact the trade of forest-risk commodities and other resources on forest legality.

Further Resource: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment: Forest Laws and Policy Database

LSE’s Grantham Research Institute has a useful Climate Change Laws of the World database, which can be utilised to search for forest-specific laws and policies. The search can be narrowed to specific regions and countries, dates and types of legislation and instruments.

Further Resource: World Resources Institute Forest Legality Initiative

This resource was created by the World Resources Institute with help from the Environmental Investigation Agency and USAID. The website contains a Document Library and country-specific information for national and regional Laws & Policies relating to forestry resources, management, products and illegal logging.

Below you will find a number of examples of country-specific national laws and codes that are directly relevant to protecting forests. However, these are only a small number of examples, and it is important to check your country’s laws as there are likely to be many more laws relevant to the protection of forests.

Brazil: Brazilian NR

This website contains unofficial translations of Brazilian regulatory standards and an easily accessible list of Brazil’s main sources of Environmental Legislation, including a number of key forest regulations and management directives.

Brazil: Brazil 2012 – Original Portuguese version & Explainer guide

This is a key example of a national forestry law that can be used to challenge deforestation. It established a land maintenance system, which dictates that a percentage of rural land must be permanently maintained as forests and prohibits the clearing of vegetation of sensitive areas. Whilst legal deforestation is allowed on privately owned land, landowners must first obtain a deforestation licence from the government. Any deforestation that occurs without a licence is illegal. The Forest Code promotes environmental compliance (with the Rural Environmental Registry/CAR) and recognises the jurisdiction of state environmental agencies (OEMAs). An amended/new Forest Code has been in force since 2012. See further WWF guidance, “Brazil’s New Forest Code, Guide for Decision-makers in Supply Chains and Governments.”

The following elements must be considered to bring an action against forest clearance under Brazil’s Forest Code:

-

The permit required for forest clearance is unambiguous and details the clearance process;

-

All forested lands are subject to an environmental and social evaluation of whether clearance is appropriate;

-

The timeframe for when to apply for a clearance permit is explicit and consistent across all relevant laws;

-

The rights of local communities and Indigenous Peoples to participate in decision affecting their land and resources are upheld; and

-

Laws are accompanied by strong enforcement and dissuasive penalties.

Brazil Case Example: Public Prosecutor’s Office v. H. Carlos Schneider S/A Comércio e Indústria & Others

Civil proceedings were filed against a group responsible for draining and clearing a mangrove forest and replacing it with landfill and other structures. The Forest Code of 1965 and Article 225 of the Federal Constitution of 1988 provided the legal basis for the court’s decision.

The Court declared that the destruction of the mangroves was illegal and ordered the defendants to restore the forest. It noted the ecological, social and economic function of the mangroves and the importance of preserving them.

Republic of Congo : Law No. 33-220 of July 8, 2020 on the Forest Code

The Republic of Congo recently passed a new law which governs the fundamental principles of the organisation and management of national forests in Congo. It also establishes rules for the exploitation and marketing of forest products and resources. Finally, the Forest Code recognises the statutory rights of local communities and Indigenous Peoples over the nation’s forests.

Chile: Decree Law No. 4.363 of 1931 (also known as the Forests Law) and Decree Law No. 701 of 1974

The 1931 law recognises the importance of the forests from an ecological, economic and social point of view, and applies to forest planted before 1974. It prohibits a number of activities including the cutting of native trees or shrubs and woodlands which are located near certain natural springs and on certain types of slopes. The 1974 law promotes forestry plantations whilst placing an obligation on owners to establish a management plan approved by the National Forestry Corporation prior to any intervention, e.g. felling (in natural or plantation forests).

India: National Forest Policy 1988

The core obligation under this Policy is to ensure environmental stability and maintain ecological balance of State Forests. Within this, existing forests and forest lands should be fully protected, and their productivity improved. The national goal is to have forest or tree cover across a minimum of one-third of total land area. For more information as to policy updates in India, see here.

National legislation may also designate forest land as a “protected area”. Where forest use takes place in a protected area, there may be further national procedural requirements or a complete ban on deforestation or degradation. Forest use can be challenged if these requirements or the prohibition are broken.

The relevant law for protected areas can be found within international and regional conventions or national legislation on protected areas and habitats. There also exist a number of international, regional and national instruments that create special protections for a given area.

Key Resource: World Database on Protected Areas

The WDPA is the most comprehensive global database of marine and terrestrial protected areas. It is updated on a monthly basis and includes protected areas designated under both international and regional conventions.

Further Resource: IUCN

The IUCN provides a key definition of protected areas, which are a clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values.

Designating a place as a protected area enables actors to conserve biodiversity and protect local community livelihoods whilst protecting vital ecosystem services such as food, clean water supply, medicines and protection from the impacts of natural disasters such as floods. Protected areas are also vital for the mitigation of and adaptation to climate change; the IUCN notes it has been estimated that the global network of protected areas stores at least 15% of terrestrial carbon.

The IUCN has a number of helpful resources on protected areas, found here.

Forest land may fall (fully or partially) within the following categories of protected areas:

- Strict nature reserve;

- Wilderness areas (i.e. largely unmodified areas without permanent or significant human habitation);

- National parks;

- National monuments or features;

- Habitat/species management areas;

- Protected landscapes/seascapes; and

- Protected areas with sustainable use of natural resources

These areas are classified according to their management objectives. They are often incorporated into a country’s national legislation. Designating forest land as a protected area may require states and relevant authorities to undertake a number of activities including:

- Biodiversity conservation;

- Inclusion of local communities in protected area governance; and

- Ecosystem maintenance.

If a state allows environmentally degrading activities to occur in a protected area or fails to do any of the specified activities, it may violate its national forestry legislation and principles of public and constitutional law.

Case Example: Wilpattu Judgement

The petitioner, a conservation and environmental justice organisation, brought a case concerning the clearing of forest land and development of displaced person settlements in the reserved forests in and nearby Wilpattu National Park in Sri Lanka. The case was brought against a number of public officials including those representing the Department of Forest Conservation, Department of Wild Life and the Minister of Industry and Commerce. Section 7 of Sri Lanka’s Forest Conservation Ordinance prohibits certain clearing and development activities in reserved forests. Article 27(14) of the Constitution requires the State to protect, preserve and improve the environment for the benefit of the community and this obligation extended to public officials and representatives.

The Court concluded that the re-settlement of displaced persons in this area violated the Forest Conservation Ordinance.

Case Example: Mining and Environmental Justice Community Network of South Africa and Others v Minister of Environmental Affairs and Others

A South African Cabinet minister approved the development of a coal mine in the Mabola Protected Environment, which is a high-yielding water catchment area that is designed as a protected area under the Protected Areas Act. The claimants sought judicial review of this decision on a number of grounds including transparency, procedural unfairness and failing to take relevant considerations into account. The Pretoria High Court set aside the ministerial approval. This decision was upheld in the Constitutional Court, which refused to hear the mining company’s’ appeal in 2019.

For more information on how you can use your national law and codes to challenge infrastructure projects (e.g. development and mining projects) that cause unauthorised or illegal deforestation, see Sub-Page 5 «Acquisition of Forest Land/Rights in Forest Land» of this Guide.

B. Constitutional and National Human Rights Relevant to Forests

Human rights are the rights and freedoms held by every human being without discrimination. Human rights protect our basic needs and freedoms.

In most countries, there are laws that protect human rights and Indigenous Peoples’ rights (for an overview of IP rights, please see section C of this subpage). These are often found in a country’s constitution but can also be found in your country’s national human rights laws. These laws are generally enforced in national courts.

- There may be rights protected in your national constitution that may also be protected in international human rights law, such as the right to a healthy environment; and

- International human rights laws may not create legal rights or obligations which are enforceable in national courts, whereas rights under national constitutions are often enforceable in national courts.

Key Resource: Constitute Project

This database contains an open-access compilation of the world’s constitutions. Constitutions can be filtered by topic (including “protection of environment” and “Indigenous rights”) and by country.

(i) What Human Rights are Impacted by Deforestation?

Deforestation and associated forest degradation pose a serious threat to the enjoyment and exercise of our human rights. As deforestation is intimately connected to rising greenhouse gas emissions and levels of carbon in the atmosphere, many of the threats posed by deforestation are also related to climate change.

Resource: Impacts of Deforestation and Forest Degradation

This resource from WWF is a useful summary of the wider impacts caused by deforestation. As forests are carbon sinks, they help to mitigate the emission of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. However, when forests are cut down, burned or cleared through other means, they emit carbon rather than absorbing it. This causes a number of serious threats to human wellbeing, including rising temperatures, changes to weather patterns and water cycles and increased likelihood of extreme weather events such as drought.

Resource: Human Rights Impacts of Deforestation

The Forest Peoples Programme provides a useful summary of some of the human rights impacts of deforestation, as well as a number of country-specific policy papers, case studies and facts on the topic.

The following human rights are most clearly affected by deforestation and degradation:

- The right to life: Deforestation poses a threat to human life and Indigenous Peoples due to its contribution to environmental degradation and climate change. A higher incidence of mortality is associated with extreme weather events, increased heat, drought and disease.

- The right to health: Deforestation increases pollution and causes loss of sources of traditional medicines. It also brings humans into closer contact with wildlife, and there is evidence of an increase in vector-borne diseases linked to deforestation. Climate change also presents a number of health-related impacts linked to extreme weather events, natural disasters and nutritional deficits linked to food shortages and loss of livelihood.

- The right to a healthy environment: Deforestation severely impacts ecosystems, threaten biodiversity and habitats and contributes to pollution and soil degradation.

- The right to water: Deforestation and forest degradation increase greenhouse gas emissions which contribute to changes in patterns of water availability and drought. Trees also play vital roles in sustaining water cycles. In addition many activities associated with deforestation, such as mining or intensive agriculture, themselves may use very large quantities of water

- The right to food: Clearing trees from the land impacts soil quality and can contribute to soil erosion, which in turn impacts crop production and yields. Many of the crops planted in place of deforested land also contribute to soil erosion. The contribution of deforestation to climate change can also result in the declining the availability of food.

- The right to self-determination: Deforestation threatens the existence and traditional livelihoods of Indigenous Peoples and communities. It compromises Indigenous People’s rights to use traditional land and resources as they choose and infringes on Indigenous People’s rights to self-government through the eradication of customary rights and land use conversion plans.

- The right to culture and religion: Deforestation infringes upon traditional knowledge, traditional livelihoods, access to traditional resources and cultural heritage (i.e. the destruction of sacred sites or areas of cultural importance).

- Land, property and territorial rights: Deforestation impacts Indigenous People’s collective rights to own, control and manage their customary lands, territories and resources. In some cases, deforestation has disrupted livelihoods and cultures and has contributed to social conflict, loss of land rights and forced displacement/migration. The customary titles of Indigenous Peoples must be recognised on an equal basis with other forms of title such as individual private property.

- The right to development: Deforestation impacts the right to improve their wellbeing, as both a process and an outcome.

The Right To a Healthy Environment

A number of countries’ constitutions guarantee the right to a “healthy, clean and/or satisfactory” environment. The following examples outline the different ways that a country’s constitution may establish a right to a healthy environment and place duties on the state to fulfil this right.[1]

Example: Constitution of Colombia

Title II, Chapter III, Article 79 states: ‘Every individual has the right to enjoy a healthy environment. An Act shall guarantee the community’s participation in the decisions that may affect it. It is the duty of the State to protect the diversity and integrity of the environment, to conserve the areas of special ecological importance, and to foster education for the achievement of these ends.’

Example: The Interim Constitution of Nepal 2063

Article 16(1) states: ‘Everyone has the right to live in a clean environment’

Article 35(5) Policies of the State: ‘The State shall make such arrangements as may be required to keep the environment clean….The State shall make arrangements for the protection of, sustainable uses of, and the equitable distribution of benefits derived from, the flora and fauna and biological diversity.’

Example: Constitution of the Republic of Angola 1992

Article 24 states: All citizens shall have the right to live in a healthy and unpolluted environment. The State takes the requisite measures to protect the environment and national species of flora and fauna throughout the national territory and maintain ecological balance. Acts that damage or directly or indirectly jeopardize conservation of the environment is punishable by law.

Even though these provisions do not provide an absolute an unqualified right to a healthy environment, they may be used as a basis for legal action on forest protection.

Case Example: Sentencia 460-2018 de la Corte Suprema de Justicia, Sala de Casacion Civil, M.P. Luis Armando Tolosa Villabona (2018)

This case was brought by Andrea Lozano Barragan and others against the President of Colombia and others. The petitioners asserted the increased deforestation in the Amazon threatens their rights to life, health and a healthy environment (including that of future generations and non-human subjects).

The Supreme Court decided that the claim could be brought on the basis that a violation of a group’s collective rights resulted in the violation of individual human rights. The Court ruled that ‘environmental protection intrinsically entails the safeguard of supralegal guarantees’ and fundamental rights such as the right to life are connected to the well-being of the environment and ecosystems. Moreover, ‘without a healthy environment, the subjects of rights and sentient beings in general will not be able to survive.’

Rights of Nature

One further right(s) that offers a potential opportunity to combat deforestation and degradation are the Rights of Nature. Whilst these are not human rights, they are protected in some countries’ constitutions and may place duties on the state to protect the rights of nature itself.

Key Case: Caso Nro. 1149-19-JP/21: Revisión de Sentencia de Acción de Protección Bosque Protector Los Cedros

In June 2020, Constitutional Court of Ecuador, agreed to take on a landmark case brought by communities near Los Cedros Reserve against the government on the grounds that its concessions for mining exploration and exploitation projects violate the Rights of Nature enshrined in the Ecuadorian constitution.

Ecuador’s highest court upheld the rights of nature as enshrined in the country’s constitution. The court held that the rights applied across Ecuador, as opposed to protected areas specifically.

The claimants had to prove their standing. See the section on “Standing” for more information on this area.

Example: Panama

In 2023, new legislation will come into force in Panama, which sets out an explicit definition of “nature” and its right to exist. The law will require the government’s future domestic and foreign policies to align with and promote the rights of nature and ecosystems.

[1]https://www.iucn.org/backup_iucn/cmsdata.iucn.org/downloads/constitutional_provisions_related_to_environment_conservation___a_study.pdf

(ii) What Are My Government’s Relevant Human Rights Obligations?

Governments have an obligation to respect, protect and fulfil their human rights obligations related to forests.

- Respect: This obligation requires government not to take action that interferes with your human rights.

- You will need to prove that the interference with your rights was not justified

- Protect: This obligation requires governments to take action to prevent third parties (e.g. corporations, individuals) from interfering with human rights

- For example: Government has obligation to adopt and enforce laws regulating corporations, ensure they are held accountable and that people receive a remedy when deforestation interfere with human rights

- You will need to prove that the government has not taken reasonable steps to prevent, investigate, punish or provide access to remedies

- Fulfil: This obligation requires governments to take conservation measures to promote sustainability of forests and restore ecosystems

- You will need to prove that the government has not taken reasonable steps in view of available resources

Case Example: Sentencia 460-2018 de la Corte Suprema de Justicia, Sala de Casacion Civil, M.P. Luis Armando Tolosa Villabona (2018)

This case was brought by Andrea Lozano Barragan and others against the President of Colombia and others. The petitioners asserted the increased deforestation in the Amazon threatens their rights to life, health and a healthy environment (including that of future generations and non-human subjects).

The Supreme Court decided that the claim could be brought on the basis that a violation of a group’s collective rights resulted in the violation of individual human rights. The Court ruled that ‘environmental protection intrinsically entails the safeguard of supralegal guarantees’ and fundamental rights such as the right to life are connected to the well-being of the environment and ecosystems. Moreover, ‘without a healthy environment, the subjects of rights and sentient beings in general will not be able to survive.’

Case Example: Suray Prasad Sharma Dhungel v. Godavari Marble Industries and others

The respondent company’s activities were causing deforestation, pollution and environmental degradation to the Godawari forest and surrounding areas in Nepal. The Court held that a clean and healthy environment was part of the right to life under the constitution of Nepal. It ruled that the respondents must take action in the public interest to protect the air, water sound and environment and specifically, to protect the environment of the Godawari area.

See the A4J Environment and Land Modules for a broader picture of a state’s environmental and land related human rights obligations.

(iii) What Right Should I Base My Claim On?

In deciding which rights to base a forests defence litigation claim on, you need to consider:

- How does deforestation or degradation affect my human rights?

After you have gathered evidence about the impacts of deforestation and degradation in your country or region, think about the impacts outlined in the Introduction to this Guide and the list of rights above. Then narrow down the most relevant rights to your factual situation.

For example, if you are a member of an Indigenous community and deforestation has forcibly displaced you from your land, the right to culture, religion, land, property, and related territorial rights may be most relevant.

- What human rights are legally enforceable in my country?

After you have identified the most relevant human rights, you need to check which ones are legally enforceable in your country. Although human rights are universal in principle, they may not all be recognised in a law that you can enforce.

If you want to enforce a human right in national courts, it must generally be contained in:

- Your national constitution or national human rights laws; and/or

- An international or regional human rights treaty which your state is a party to and is directly enforceable in your country.

If you are bringing a case regarding a national human right, you may have the option of going to a regional/international body if you don’t succeed at the national level. For more information on International and Regional Human Rights related to deforestation, see Sub-Page 3 International/Regional Laws and Conventions of this Guide.

Additionally, in the event you are enforcing rights protected in a national constitution through domestic courts, the interpretation and application of that right to your case could be influenced by how similar rights are understood and enforced at both the international level and through a comparative perspective (i.e. how national courts in other countries have approached similar perspective). For more information on how international law can be used in national courts, see What Laws Could I Enforce in the A4J Going to Court Guide.

(iv) How Can I Argue that the Government Has Violated My Human Rights?

Once you have identified a relevant and legally enforceable right, you need to argue that the government has violated that right. This means that it has breached the human rights obligations it owes you.

For this argument to be successful, you usually need to show:

- There has been an interference with your enjoyment of a human right. This means that deforestation has affected your rights. You must show the impact on your enjoyment of the human right has (i) reach a minimum threshold of seriousness; and (ii) is caused by deforestation or activities causing forest degradation. To demonstrate this, it will be important to have evidence of the legal test and threshold of seriousness to meet in your country, past cases which has reached this threshold, and deforestations impact on you; and

- The interference cannot be justified. Governments may try to justify deforestation and degradation on the basis of development goals or economic well-being. You must show that the government’s actions were an unreasonable or disproportionate way to achieve these objectives when compared to the impact their failure has had on your rights. This will be a highly contested and fact sensitive argument.

Case Example: Sheikh Asim Farooq v. Federation of Pakistan

A group of citizens filed a petition against the Pakistani government for violating their rights by allowing widespread deforestation and endangering the climate. They argued that the government’s failure to follow its own environmental policies and obligations to protect the forest violated their constitutional rights to life, dignity and access to public places of entertainment and provision of leisure places.

C. National Indigenous Peoples’ Rights

Indigenous Peoples and local communities are fundamental for the protection and preservation of forests across the world. However, many Indigenous Peoples and communities are disproportionately subjected to socially, economically and environmentally harmful deforestation as a result of logging, mining and other development activities. These activities negatively impact the livelihoods, land and rights of Indigenous Peoples. [1]

At the national level, Indigenous Rights are often incorporated under national procedural and substantive bodies of law, such as laws that protect land rights. However, some countries enshrine Indigenous rights and specifically, the right to consultation and, where available, the right to free, prior and informed consent in their national legislation.

Example: The Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act of 1997 (Philippines)

This Act was created to recognise and promote all the rights of Indigenous Cultural Communities and Peoples within the framework of the Constitution. Lands possessed by these groups include ancestral and forest land.

The requirement for the communities’ and individuals’ free, prior and informed consent in matters affecting these lands is established in Section 58.

Those looking to bring a claim to their country’s national courts based on their rights as Indigenous People should check your country’s national forestry laws, land laws, constitutions, specific laws relating to Indigenous rights (if any), and national human rights obligations to determine what cause of action might suit you best.

Case Example: Policy for Territorial and Environmental Protection of Indigenous Lands (PNGATI) (Federal Decree 7.747/2012)

This is a Brazilian policy that aims to guarantee and promote the rehabilitation, conservation and sustainable use of Indigenous Land and territorial natural resources. It also aims to ensure the integrity of Indigenous land property, improve the quality of life and the physical and cultural conditions for present and future generations of Indigenous People.

For more information on Indigenous rights and deforestation, see Acquisition of Forest Land/Rights in Forest Land in Sub-Page 5 of this Guide.

[1] https://amazonwatch.org/news/2020/0702-mining-on-indigenous-territories-brings-devastation

Who Can Bring a Claim?

In order to bring a constitutional, public law or human rights claim, you must have “standing” (the legal right to bring a claim).

See Sub-Page 4 of this Guide for more information on standing.

TIP: Often the person or organisation that ought to bring a claim to enforce forest laws is a state prosecutor, or state department such as an environment protection agency. Sometimes the best way of protecting the forest is not to take legal action yourself but to ask a government agency to do so. However, these agencies are unwilling to take action to stop illegal activities. This may be due to lack of resources of knowledge, corruption or political pressure. Sometimes legal action can be taken against these agencies to compel them to take action to enforce the law.

Who Can I Bring a Claim Against?

For claims based on constitutional, public law or human rights, the appropriate defendant could be:

- The State as a whole (i.e. your country);

- The government department, ministry or body that is responsible for deciding forest and/or environmental policy in your country;

- Corporate defendants, depending on the facts of the case and the laws or codes engaged.

For further information, see “Who Can I Bring Legal Action Against” in the A4J Going to Court Guide.

What Evidence Do I Need to Bring a Claim?

In public law actions, it is the claimant (e.g. you) who has the “burden of proof”. This means the person bringing a civil claim needs to bring evidence to prove their case.

One of the first things you need to do to bring a successful claim is gather evidence that will be accepted in court. You must have a set of facts that describes what happened and evidence that supports your “version of events” (i.e. what you are saying happened). This is called “factual evidence” and will be used to support your claim.

You will need to ensure you have specific evidence of:

- National environmental or climate change policy that relates to the conservation, maintenance or protection of forests and protected areas;

- National policies (if any) that relate specifically to deforestation;

- Deforestation activities in an area by a government body/authorisation of deforestation by a government body AND/OR evidence of your government failing to take action to prevent deforestation;

- The impacts of deforestation on you (e.g. your land, property, health or finances); and

- Evidence of the ecological impacts of deforestation in your area.

For further information on evidence, including the scope of evidence you will need to provide, see the section on “Evidence and Information” in Sub-Page 11 of this Guide.

For general information on evidence, see the section on “How Can I Prove My Case” in the A4J Going to Court Guide.

What Procedural Steps Do I Need to Take?

These claims are usually taken in national administrative or constitutional courts.

- In some countries, this process is called “judicial review” or a “constitutional petition”.

- In many Latin American countries, this process is called “amparo proceedings”.

The procedure that you must follow will depend on whether you live in a “common law country” or “civil law country”. The law in your country will outline a judicial review, constitutional petition or amparo process, so that you can bring a claim to the courts and the court may review the situation and provide a remedy.

Focus Point: Limitation Periods

A limitation period imposes a time limit within which a claimant may bring a case. The limitation period depends on the precise cause of action and will dictate the amount of time you have to file your case in court. If you do not file your case within the relevant limitation period, you may be prevented from bringing the claim.

Research the law in your country to determine the relevant limitation period for your claim. You will also need to identify when the time starts running for the limitation period. Time may start running from one of the following:

- The date the harm occurred (e.g. when a forest fire occurred);

- The date you learned about the harm; or

- The date the government made the specific policy decision or took an action that you are challenging.

In some cases, it may be possible to apply for the limitation period to be extended.

For more information, see “What Procedural Steps do I need to take” in relation to Administrative, Constitutional and Human Rights Cases in the A4J Going to Court Guide.

What Happens if I Win?

A. Remedies

If you bring a successful claim against the government in public law, human rights or constitutional law, you may be entitled to one or more of the below “remedies”. The outcome of a successful case will depend on your cause of action and specific claim:

- (i) Declaratory Judgment: the Court may be able to issue a declaratory decision that the government or public body has acted unlawfully. However, a declaratory judgement does not tell the government what to do.

- (ii) Court Order: If the Court finds that your country has violated its national laws, it may order the government to take a certain type of action. This may include:

- Demand the government take action to stop deforestation;

- Demand the government follow proper procedures in authorising deforestation; or

- Require the government to commit to returning the deforested area to an acceptable state, e.g. through reforestation or afforestation plans.

- Require the government to pay compensation for the harm caused by any damages and evictions.

Case Example: Future Generations v. Ministry of the Environment and Others

The Court ruled in favour of the claimants and order the government to form a plan of action to combat deforestation; create an intergenerational pact for the Colombian Amazon (including measures to reduce deforestation and greenhouse gases to net zero); and to take immediate action to stop deforestation.

Case Example: Sheikh Asim Farooq v. Federation of Pakistan

Ruling in favour of the claimants, the judge ordered the Pakistani government to uphold its environmental laws and climate change policies, including its obligations to protect the forest. The judge also ordered the government to publish annual reports on progress of reforestation, punish those who illegally cut down trees and take disciplinary action against public officials who fail to carry out their duties.

If you have brought a successful case under Indigenous Peoples’ rights, you may be granted the above remedies as well as:

- Granted an order declaring that you have ownership of the land and native customary rights over the land (for property rights claims); or

- Given compensation or reparations.

Case Example: Brazil’s Ashaninka Deforestation Settlement

The Ashaninka people in the state of Acre in the Brazilian Amazon received reparations for deforestation that occurred on their lands in the 1980. The logging company, which supplied Europe’s furniture industry, was owned by the family of the current governor of Acre. The case involved a number of constitutional questions, including the right to a decent life.

It is important to remember that the affected individuals and communities should lead on deciding which remedies are appropriate, as opposed to NGOs or lawyers. For most communities, restoration of their land, or rights over their land, is the main priority. Consider the community impacts of each possible remedy.

For more information, see our general page, “What Remedies Are Available?” in the A4J Going to Court Guide.

B. Enforcement

Winning in court is only the start of the process. Many successful court judgments are either not enforceable or are not enforced in practice.

You may be able to go back to court and ask for the judgement to be defined and enforced. See the general page on “How Can I Enforce a Court Order” in the A4J Going to Court Guide.

Other Issues, Solutions and Practical Tips

In addition to all the factors above, there are further practical issues you need to consider.

One set of issues relates to the resources you will need by way of general support for you, and the case, legal and expert advisers, finance, logistics (such as transport), translation and printing.

Another set of issues is on the safety and security of you, witnesses and your information.

For general guidance on these, see the relevant headings in Sub-Page 11 “Going to Court” of this Guide.