Climate Litigation Basics

So far, we have introduced you to the causes and impacts of climate change, as well as what needs to be done to prevent dangerous climate change. The Guide will now take you through what legal options may be available to combat climate change and some of the basics to get you started if you are thinking of pursuing legal action.

What Is Climate Litigation?

Climate litigation means legal action that aims to combat climate change and involves arguments which are related to climate change. Climate litigation is one tool communities and individuals are using to force governments and corporations to do more to prevent dangerous climate change.

(a) Are People Taking Climate Litigation?

Climate litigation is growing fast across the world. A recent report from the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and the Sabin Centre for Climate Change Law details that, as of July 2020, there were more than 1,213 cases filed in the United States and over 374 cases brought in other countries.

Key Resources:

To find out more about the latest developments, look at the sources below:

- The Sabin Center Climate Litigation Database: Columbia Law School’s database provides a comprehensive collection of different pieces of climate litigation brought across the world.

- Climate Liability News: A website that provides updates on new climate litigation cases.

- Climate Change Laws of the World Database: LSE, the Grantham Research Institute and the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law have a database on climate litigation and climate laws/policies around the world.

- New Model Statute For Citizens to Challenge Governments Failing To Act on Climate Change (IBA 2020): The Model Statute provides a number of rationales, precedents/authoritative decisions and articles that would support climate litigation for the reduction of greenhouse gases.

(b) What Different Types of Climate Litigation Are There?

For an overview of the key elements of the most common types of climate litigation, see the Action4Justice Climate Litigation Matrix.

Please note that different forms of litigation are not mutually exclusive. For example, you may be able to target inadequate action in both mitigation and adaptation.

(i) Mitigation Claims

These are legal cases brought against governments of countries who have significantly contributed to climate change and are accused of failing to take sufficient action to reduce their GHG emissions (i.e. to take mitigation measures).

Example: Urgenda Foundation v Kingdom of the Netherlands

A Dutch environmental group and 886 citizens sued the Netherlands for not taking enough action to reduce their GHG emissions.

In 2019, the Dutch Supreme Court found that the Dutch government must, by 2020, have reduced their GHG emissions by at least 25% from 1990 levels. The government’s failure to do this was a violation of the rights to life and private life protected under the European Convention on Human Rights.

This Guide will go into detail about how you could bring this type of claim in Legal Action to Get My Government to Reduce its Emissions.

(ii) Adaptation Claims

These cases involve forcing governments to take adaptation measures to protect communities from the impacts of climate change that are already occurring or will occur, for example from life-threatening extreme weather events.

Example: Leghari v Republic of Pakistan

A case was brought against government authorities in Pakistan by a local farmer for their failure to put in place sufficient adaptation measures and the resulting damage to his livelihood.

The Court held that Pakistan had violated citizens’ rights to life, dignity and property and ordered the government to take measures to minimise the impacts of changing weather patterns, including presenting a list of climate adaptation measures and to establish a Climate Change Commission.

A related type of climate ligation is against specific public authorities or private companies who have a duty to protect citizens against the effects of climate change. These could involve claims against engineers or government departments responsible for building adequate flood defences, architects responsible for buildings that consists withstand extreme weather events, and fire departments responsible for constructing fire breaks or fire defences. When these groups fail to carry out their legal duties, they may be liable to those damaged by that failure.

This Guide will go into detail about how you could bring this type of claim in Legal Action to Get My Government to Take Adaptation Measures.

(iii) Challenges to Carbon-Emitting Projects

These are cases brought against public bodies who have licensed resource extraction or infrastructure development which will significantly contribute to climate change (e.g. coal mines, oil drilling, fracking, dams, roads or airports etc).

Example: EarthLife Africa Johannesburg v Minister of Environmental Affairs

An environmental organisation in South Africa successfully challenged the opening of a new coal mine on the basis that the responsible public body failed to take into consideration its climate impacts when licensing the project.

This Guide will go into detail about how you could bring this type of claim in Legal Action to Challenge Carbon-Emitting Projects.

(iv) Claims Against Carbon Majors

These are cases brought against big corporations who have significantly contributed and continue to contribute to climate change. These cases can ask for corporations to contribute to the cost of responding to climate impacts, compensation for damage, or for orders to change restrict their actions.

Example: Lliuya v RWE AG

A case brought by a Peruvian farmer in German courts against RWE (a German energy company) for their contribution to climate change and its impact on glacial melts and flooding of his community. They demand that RWE contribute to adaptation costs required to protect against flooding.

This Guide will go into detail about how you could bring this type of claim in Legal Action to Hold Corporations Accountable for Contributing to Climate Change.

(v) Investor and Financial Claims

Investor and financial claims involve a range of different forms of climate litigation. This includes legal action against institutions that finance carbon majors or carbon-intensive projects, such as shareholders, banks, pension funds and others.

It can also involve legal action brought by shareholders and investors against Carbon Majors because of their continued engagement in carbon-intensive activity or because of their lack of transparency on their climate policies or emissions.

Example: ClientEarth v ENEA

The Claimant, an environmental organisation, purchased some shares in the defendant company and sued it in its capacity as a shareholder in Poland.

The Claimant argued that a proposal by ENEA to construct a new coal plant risked breaching board members’ fiduciary duties of due diligence and to act in the best interests of the company and its shareholders because of the poor financial prospects of the proposed coal plant. These poor financial prospects were based on rising carbon prices, increased competition from renewable energies and increased regulation of the industry.

The Polish court agreed and found the plans for the new coal power plant to be invalid.

This Guide will go into detail about these types of claims in Investor and Financial Claims.

(vi) Alternatives to Court

This Guide will also address other climate-related complaints that do not strictly amount to climate litigation. These are often complaints to “non-judicial bodies” which can hear complaints against governments or corporations.

Examples include:

- Complaints to OECD National Contact Points against corporations;

- Complaints to National Human Rights Institutions against governments or corporations; and

- Submitting reports to International Human Rights Bodies to evaluate government climate action.

This Guide will give more information about these types of complaints in Alternatives to Going to Court.

(vii) Other Types of Litigation

This Guide does not intend to go into detail on every type of litigation that could be taken to address climate change. As the effects of climate change are increasingly felt and calls for climate justice grow louder, it is likely that more and more types of claim will be developed and be successful. Below are some examples of areas of law to watch in case of potential developments:

- Competition and anti-trust law: Although the cost of renewable energy is falling, carbon intensive companies and economies may have at least a short-term economic advantage over low carbon equivalents. It may be possible to argue that this infringes national or regional competition or anti-trust laws.

- Criminal law: Where corporations or public officials provide false information on climate change they may attract criminal or regulatory liability. Also such proceedings are usually brought by public authorities, this may be as a result of a complaint from an ordinary citizen.

- Insurers’ liability: Insurers have a huge influence on how industry and commerce operate. If insurers continue to cover carbon-intensive industries, it could be possible for persons affected by the operation of a company’s activities to bring an action direct against its insurers.

It should also be remembered that there are other types of litigation which can help combat climate change but are not considered climate litigation.

- For example, there may be plans for a large coal mine to be built on a site which is the habitat of an endangered species of frog. The members of the local Climate Justice Campaign may be more concerned about climate impacts of the mine than the impact on the frogs, but taking legal action based on a law protecting the frog’s habitat may be the most effective legal strategy to stop the mine and its climate impacts.

These types of litigation will not be covered in this Guide.

(c) What Impact Can Climate Litigation Have?

Climate litigation is only one tool that we can use to secure climate justice. Political action, campaigning and economic initiatives will also be key. Nonetheless, climate litigation can have a big impact.

Depending on what type of case you bring, a successful climate litigation case could result in:

- Governments having to take action to reduce national GHG emissions;

- Governments having to take action to protect vulnerable communities from climate impacts;

- Big carbon projects being cancelled, leading to reduced GHG emissions;

- Corporations being held accountable for their contributions to climate change, being made to either pay or change their business operations; and

- Financial divestment from the fossil fuel industry.

An important point to understand about some forms of climate litigation and some of the above outcomes is that their purpose is to effect change for the benefit of society as a whole and future generations and not just for the direct benefit of those bringing the claim.

- In other types of environmental cases, claims can be brought by people close to a mine or factory to stop pollution from it. The pollution affects the local people, and if they win, they benefit because it stops.

- Some types of climate litigation are different. Winning or losing a claim to reduce your government’s GHG emissions or hold a corporation accountable for its contribution to climate change will generally have no immediate benefit for the people bringing the case, but it will contribute to the broader goal of preventing dangerous climate change.

Climate litigation is new, complicated and difficult. Many of those who bring a case to court don’t win. But even unsuccessful climate litigation (i.e. that lose in court) can have an impact:

- Although an overall case might lose, a court can make a helpful finding (e.g. accepting the climate science in your case) that future cases can build on; and

- They raise awareness about climate change and increase pressure for governments/corporations to change their actions.

However, sometimes the opposite can occur. A poorly thought out action can set a helpful precedent for those opposed to adequate emission reduction or have an adverse effect on a campaign. Before taking any action, it is necessary to think through the possible benefits and possible risks. This guide is designed to help do this.

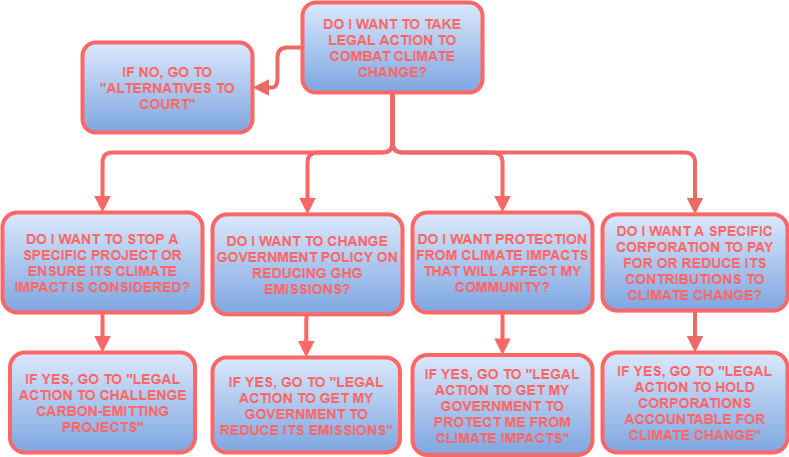

What Type of Claim Is Right for Me?

A good first step in deciding what type of claim might be right for you is thinking about what outcome you would like to achieve from your case as shown in the table below.

After you think about outcomes, you can then focus on practicalities or legal issues which may change the type of claim that’s right for you. The remaining sections of the Guide will help put you into a position to decide what type of legal action is right for you.

The Building Blocks of Successful Climate Litigation

Before the Guide goes into details on tips and strategies for specific types of climate litigation, below you can find some general tips that can apply to most climate litigation cases.

(a) Base Your Claim on the Best Climate Science

Climate science provides the foundation of evidence on which you can build your case. In any climate litigation case, you must establish before a court that:

- Climate change is occurring;

- Climate change is caused by man-made GHG emissions; and

- Climate change has serious impacts on ecosystems and/or human lives.

An important source that represents that scientific consensus on climate change is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Courts have relied on IPCC reports in several cases.

Key Resource: The IPCC Reports

The IPCC is an international body for assessing climate science. Hundreds of leading climate scientists take part in it, and 195 representatives of countries are members of the IPCC, giving its findings exceptional weight.

The IPCC conducts scientific assessments of existing climate science. Its findings provide the basis for all the major international agreements on climate change. The IPCC’s “assessment reports” outline the occurrence, causes and impacts of climate change. The reports also outline the amount countries need to reduce their GHG emissions by to prevent dangerous climate change.

Countries are adopting the recommendations of the IPCCs reports, meaning that these assessments also represent the political consensus on climate change science. For these reasons, they offer a great starting point in gathering evidence on which to base your litigation.

In addition to the IPCC reports, the following sources also provide strong evidence:

- Studies by respected scientific institutions such as NASA, the WMO, the Union of Concerned Scientists;

- Reports by respected international organisations such as the World Bank, the IMF and United Nations bodies;

- Peer-reviewed scientific journals such as LANCET, the European Academics’ Advisory Council, Nature, Science, and AmetSoc.

If you are taking climate litigation, you will usually also need to gather evidence about the specific impacts that climate change is having on your country, region or community. Useful sources of evidence to demonstrate local climate impacts often include:

- Local attribution studies which connect the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events with the occurrence of climate change (“attribution science”);

- Reports by governmental bodies and regional organisations on the national/regional impacts of climate change;

- Peer-reviewed scientific studies focusing on the impact climate change is having in your area.

Science is important in shaping climate litigation strategy on two important climate liability issues. These issues are important elements of attribution science. It is helpful to provide scientific evidence on both elements:

- Source Attribution: To what extent are the GHG emissions that are causing anthropogenic climate change the defendant’s responsibility (whether it is a corporation or a government); and

- Impact/Event Attribution: To what extent the specific injuries or harms suffered by the claimant are attributable to the defendant’s contribution to climate change.

Key Evidence: Event Attribution Science

This refers to scientific studies that seek to determine the extent to which climate change has influenced the probability or severity of a weather event or type of weather event (e.g. forest fires, heatwaves or floods).

Event attribution science may be useful in proving that you are specially affected or threatened by a certain extreme weather event and that this event is connected to climate change.

In the remaining sections of the Guide, we will outline additional evidence that can be helpful for different claims.

(b) Establishing Jurisdiction

For a court to be able to hear the case you are bringing, it must have “jurisdiction” over the party who you want to sue. This essentially means that the court has the power to hear the claim against the defendant.

Depending on your case, a couple of different types of jurisdiction could be relevant:

(i) Geographical Jurisdiction

Usually, courts only have jurisdiction over defendants (persons or businesses) that are based in the country of the court or where the case concerns actions that took place in that country. This will not be a problem where you want to take legal action against your government, or a corporation based in your country.

However, issues can arise if you want to take legal action against a corporation that is based in another country. For more information on what countries’ courts may have jurisdiction over a corporation, see the A4J Business and Human Rights Guide.

(ii) Subject Matter Jurisdiction

The claim must also be of a type the court is willing to hear. In some countries, courts can refuse to hear cases then they think they are not or raise a “political question”.

- In climate litigation, justiciability could prevent your claim from being heard if the judge thinks climate policy is an issue that should be left with the executive/legislative aims of government.

- This is based on the principle of the separation of powers, which outlines what responsibilities courts, legislatures and executive bodies should have in governing a country.

Some cases have successfully overcome this requirement. A key argument in these cases has been that although a judgment might have political consequences, it only involves a “legal question”.

Example: Urgenda Foundation v The Kingdom of the Netherlands

The Dutch Supreme Court rejected the government’s arguments that the separation of powers prevents the court from interfering with its climate policy. It held that:

- The question of whether the government’s policy violated human rights was a legal question which the court had authority to decide; and

- While the court outlined the minimum the government had to do to respect human rights (i.e. reduce its GHG emissions by 25% by 2020), it left the government discretion as to how it would reduce its emissions.

To overcome the justiciability requirement, it can be helpful to:

- Emphasise that your case concerns legal rights and duties, and that it’s the court’s role to review the lawfulness of government action (i.e. the rule of law argument);

- Argue that you have a right to access remedies or reparation where a legal wrong has been committed (i.e. the access to remedies argument); and/or

- Limit the requests for relief so the government or corporations still has some room to decide how it will reduce GHG emissions.

Key Resource: The A4J Justiciability Topic Sheet

The Justiciability Topic Sheet provides an insight into how the justiciability requirement in many legal systems relates to climate litigation.

Courts may also decline to hear cases on the basis of the doctrine of “displacement” or “pre-emption”. In some countries, these doctrines mean that if a central government or legislature makes a law or regulation covering an issue, it is not possible to challenge activities relating to that issue on the basis of lower laws in the hierarchy (e.g. local or state law), older laws or more general laws (e.g. laws of civil responsibility).

For example, if government has given a national body the power and duty to regulate greenhouse gases, or has enacted statutes or regulations on climate change, the courts may decline to hear climate litigation that is based on laws of civil responsibility (e.g. tort law) or state laws. However, as explained below, if the statutory or regulatory regime itself is inadequate, it may be possible to challenge this on constitutional grounds as this is the highest form of law.

(c) Establishing Standing

The person or group bringing a legal claim (“the Claimant”) has to show that they are entitled to bring the claim. In many countries, this entitlement is called “standing”. This can be a difficult issue and climate litigation claims have been declined because the claimant cannot show a sufficient interest or stake in the issue because they have not suffered any specific or special harm from climate change or from the specific action complained about.

What types of people may have standing in different types of cases will be discussed throughout the Guide. If you would like to find out more about standing in general, see Who Can Take Legal Action? on the A4J Going to Court: Q&A.

Key Example: People’s Climate Case

This case demonstrates the difficulties claimants may encounter in showing they have suffered special harm from climate change. The EU General Court rejected the claimant’s arguments that their countries’ GHG reduction targets were too low on the basis that the claim was inadmissible because the claimants were not individually concerned by EU law on climate change (i.e. they lacked sufficient interest).

This case demonstrates the difficulties claimants can have in establishing standing in climate litigation cases, showing that in some courts, the broader the impacts of climate change, the less power courts have to adjudicate.

Key Case to Watch: Reserva Los Cedros v. Ecuador

In June 2020, the Constitutional Court of Ecuador agreed to hear an infrastructural challenge brought by Los Cedros Reserve against the government on the grounds that its concessions for mining exploration and exploitation projects violate the Rights of Nature enshrined in the Ecuadorian constitution. The claimants are also arguing that the projects violate the legal status of the Los Cedros Protected Area, collective rights of indigenous peoples and the procedural rights of communities to prior consultation before potential environmental damage.

(d) Identifying the Legal Basis of Your Claim

It is not enough to succeed in a legal claim to show that you have suffered or may suffer harm from climate change. You have to invoke either a specific legal right that you have, which has been breached, or demonstrate there is a law or legal duty on the defendant that has been broken. This legal right or law could be based on your country’s constitution, international agreements, environmental or other legislation, or general civil responsibility laws (e.g. tort laws). The most relevant laws for each type of climate litigation will be outlined through the Guide.

Key Term: Cause of Action

A cause of action is a set of facts that ground a claimant’s legal claim in court. You must have a cause of action and fulfil each legal element of your cause of action to succeed in court.

Remember that the law can change. What may not have been possible yesterday, may be possible today. Pay attention to legal changes in your country and new opportunities that could exist to bring climate cases.

In certain cases, particularly those brought against corporations based in other countries, there may be a question over which country’s law should apply to your case. For more information on this issue, see the A4J Business and Human Rights Guide.

(e) Supplementary Legal Principles

If you are pursuing climate litigation, there are some general legal principles that can support your arguments, even if they are not actually part of the law of the country in which you are bringing the claim. Courts in some countries are often willing to pay attention to arguments based on international human rights law, as well as some principles of public international law detailed below.

You are not arguing that government policy or a corporation’s actions are unlawful because they violate these principles. Rather, you are arguing these principles should influence how the court interprets and applies national law.

(i) The Precautionary Principle

This principle requires that where there is a threat of serious or irreversible environmental harm, scientific uncertainty cannot be used as a reason to delay action to prevent the harm. This principle is included in the UNFCCC and many national laws.

In some legal systems, where you can prove there is a credible risk of serious or irreversible environmental harm, the precautionary principle can reduce the “standard of proof”. This can mean that you may not have to provide as much evidence to prove that the harm will occur or was caused by a specific thing, as long as there’s evidence of a serious risk.

Although it is sufficiently certain that climate change is happening, it’s caused by GHG emissions and it will have impacts, the precautionary principle can be useful in the following circumstances:

- Where it’s not clear what the precise impact of a carbon-emitting project will be, the precautionary principle can help overcome this uncertainty;

- Where the government has different options available in dealing with climate change, the precautionary principle could help persuade the court to side with the most safe and effective option; or

- Where the level of influence climate change has had on causing a specific weather event is uncertain, the precautionary principle could be used to persuade the court that evidence generally connecting climate change to that type of weather event is sufficient.

(ii) The no-harm principle

This principle requires states to prevent transboundary environmental harm in other countries where the source of the harm comes from their territory.

- This principle can be particularly useful if you are bringing a climate case against a government in another country; or

- You want to persuade a court that it should take into account the climate impacts that your government’s actions will have in other countries when making its decision in your case.

(iii) The polluter pays principle

This principle requires those who are responsible for pollution to make good and/or bear the costs of the damage it causes. This principle is contained in many national laws and environmental regulations.

- The polluter pays principle also applies to GHG emissions.

- The principle can be useful if you are bringing a climate case against a Carbon Major.

(iv) International climate change agreements

Although international climate change agreements cannot be directly enforced in courts, key provisions from the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement can influence how national laws are applied in climate cases.

- E.g. the aims of limiting global temperatures to 1.5°C to 2°C in the Paris Agreement can be used to assess whether the government is doing enough to reduce its GHG emissions.

Example: Plan B Earth v Secretary of State for Transport

In the UK, an environmental organisation challenged the expansion of Heathrow Airport on the basis that the government failed to consider how the expansion was consistent with their commitments under the Paris Agreement.

.

(v) The rights of future generations and the principle of sustainable development

These principles require that actions of the present generations must be balanced against the protection of the environment in a way that does not compromise the needs of future generations. These principles of rights of future generations can strengthen an argument that human rights and environmental protections should be applied with a long-term view.

- For example, it could be argued consideration of the rights of future generations and environmental sustainability mean that governments should consider the long-term climate impact of projects before making licensing decisions, even if it’s economically beneficial in the short-term.

(f) Identifying an Appropriate Remedy

A remedy is a legal order that is made by a court. This may be to stop, undo or compensate for the consequences of an unlawful action or may be simply to declare that an act or decision or policy is unlawful or of no effect. Courts do not have unlimited powers to make any order they want.

Normally you have to seek an order which the court has power to grant. In climate litigation, these are usually things such as striking down or declaring a law or policy invalid, granting an order to a party to do something or stop doing something, or order payment of compensation.

It is important to remember that the affected individuals and communities should be leading the development of the climate litigation strategy and deciding which remedies are appropriate, as opposed to NGOs or lawyers. In addition to community involvement, remember to consider the community impacts of the strategy and each possible remedy.

Before you start your claim, it’s important to think about what remedy you want and whether this could be ordered by a court that can hear your claim. More information will be provided on this issue in later sections. For general information on remedies, see What Remedies Are Available? in the A4J Going to Court: Q&A.

(g) Contact a Lawyer

Climate litigation can be complicated and difficult. It is a new area of law that is constantly changing. For this reason, you will need support from a lawyer or an organisation with expertise in the relevant area of law to take a case. They will be able to help you decide whether you have a case, the strengths of your case and also on the best course of action to take.

For more information, see Where Can I Find More Information and Support? in this Guide or How Can I Get Legal Support? in the A4J Going to Court: Q&A.

(h) Paying for Your Case

All claims cost money. Bringing a claim can be an expensive and time-consuming process. This can be especially true in climate litigation, where the complexity of the cases is high. In some countries, the loser of the claim must pay the winner’s fees. In these countries, someone who brings a lawsuit and loses may find themselves facing very high expenses for the other side’s lawyers.

BUT, there are ways to help finance your claim, including legal aid, pooling together resources in a group claim, obtaining volunteer support from pro-bono lawyers or experts, or getting support from an organisation. In some countries, it’s also possible to have court fees waived in public interest cases.

We recommend that you read our webpage How Can I Finance My Action? in the A4J Going to Court: Q&A.

(i) Dealing with Threats and Security Issues

Taking legal cases in politically sensitive areas can be dangerous. You can be faced with threats when challenging governments and corporations to take climate action. This is because climate justice can conflict with powerful political and economic interests that want things to stay the same.

Before taking a case, we recommend you read How Can I Deal with Security? and How Can I Protect My Information?