Bail

This section will give you an introduction in the issue of bail, the legal framework and suggest ideas about what you could do if you or someone in your community has been detained without bail.

What Is Bail?

Bail is the conditional release of a suspect from detention. The conditions attached to bail are generally used to ensure that a suspect complies with the judicial process and appears in court when they need to.

(a) Why Is Bail Important?

Bail is important because it allows the suspect to remain in the community while their case is in the court system:

- If the criminal justice process in your country is slow, bail can be a vital alternative to being held in detention for months or years while the case is being decided; and

- By giving people an alternative to detention for people who have not been convicted of a crime, bail upholds the presumption of innocence (i.e. that everyone should be treated as innocent until they are proven guilty).

(b) When Is Bail Considered?

Bail can often be granted by a court at any point in the criminal justice process. Bail may be considered at the following stages:

- In some countries, police can grant bail when someone is arrested and brought to a police station;

- Prosecutors can decide to grant bail before the accused has first appeared in court;

- The court can grant bail when the accused first appears in court; or

- A court can schedule a “bail hearing” where bail will be considered.

(c) What Happens if I’m not Granted Bail?

If someone isn’t granted bail, they will continue to be held in detention without bail. This is often called “held on remand”.

What Is the Legal Framework?

The laws on bail are generally found in a country’s criminal procedure rules or in their constitution. It is these laws that will be relied on if you are applying for bail. It is important that you become familiar with the legal framework that relates to bail in your country before applying for bail.

(a) The Right to Bail

The starting point for thinking about bail is that in many countries is that you have a right to bail. In other words, there is a presumption you should be granted bail but there are exceptions to this.

The right to bail follows from the right to liberty is reflected in many international human rights treaties:

Example: The UN Human Rights Committee

Following from the right to liberty in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the HRC has consistently held that “pre-trial detention should be the exception and that bail should be granted, except in situations where the likelihood exists that the accused would abscond or destroy evidence, influence witnesses or flee from the jurisdiction of the State party”.

This broad presumption in favour of bail is recognised in many countries:

Example: State Of Rajasthan, Jaipur v. Balchand (India)

The Indian Supreme Court ruled that the basic rule is bail, not jail, except where there is a risk the accused may flee from justice, interfere with the course of justice, repeat offences or intimidate witnesses.

(b) Exceptions to the Right to Bail

Although there is a presumptive right to bail in many countries, this does not mean that bail will be granted in every case. This is because there are exceptions to the right to bail. It is important to know what the exceptions to bail are in your country.

(i) Bailable and non-bailable offences

In some countries, criminal offences are split into “bailable and non-bailable offences”.

- Bailable offences are often non-serious offences where an accused would not receive a prison sentence if convicted or a prison sentence of, eg, less than 3 years. In these cases, there is usually a strong presumption the accused should be granted bail, or an absolute right to bail.

- Non-bailable offences are more serious criminal offences, for example, where the accused could receive a prison sentence of over 3 years if convicted. For these offences, the accused can either not get bail at all or there is a weaker presumption they should get bail.

Example: Pakistan Code of Criminal Procedure

The Pakistan Code of Criminal Procedure distinguishes between bailable and non-bailable offences.

Bailable offences are less serious offences where a person has a right to bail, as long as they can meet the conditions that are attached to bail (bail conditions are discussed below).

The non-bailable offences are split into two categories:

(1) Offences not falling in a “Prohibitory Clause”

These are offences punishable with a prison sentence of less than 10 years. In these cases, the grant of bail is a rule but there are general exceptions, such as where there’s a risk the accused will not appear in court if released on bail (these general exceptions to bail are discussed below).

(2) Offences falling in Prohibitory Clause

These are more serious offences that are punishable with death, life imprisonment or imprisonment for ten years or more. In these cases, the general rule is that bail shall not be granted but there are exceptions for:

- People under 16 years old;

- Women;

- People with illness; and

- People with disabilities.

Check if there is a similar framework in your country.

(ii) General exceptions to bail

Even where serious criminal offences are not concerned, there are general exceptions to bail in most countries.

Example: Pakistan Code of Criminal Procedure

In Pakistan, the following exceptions to bail apply to offences punishable with a prison sentence of less than 10 years:

- The is likelihood the accused with abscond (not appear at trial);

- Where there is a risk the accused with tamper with prosecution evidence;

- Where there is a danger the offence will be repeated if the accused is released; and

- Where the accused has been previously convicted.

These are common exceptions to the right to bail. Other exceptions could include:

- Where the accused was already released on bail when they committed the offence;

- Where being held in custody is for the protection of the accused (e.g. they could be targeted if released);

- There isn’t enough information to make a bail decision;

- Where it’s necessary for the investigation to keep the accused in custody; or

- The accused has previously broken their bail conditions (see below).

(iii) Payment for bail

In some countries, there can be a further requirement that the accused deposits an amount of money set by the court as a condition of their release. This is a form of deposit sometimes called a “security”, “bail bond” or “cash bail”.

In many countries, a “security” can be ordered as part of a set of bail conditions (see below) but it is not a strict requirement and the inability to afford a security will not necessarily mean someone cannot get bail.

However, in a small number of countries, a “bail bond” is a stricter requirement and can result in people without means being held in detention without bail for non-serious crimes.

Example: Philippines Bail (Rule 114) Nature

In the Philippines, the following types of bail are common:

- Corporate bond: The bail security is covered by the company of the accused;

- Property bond: The accused has to put up property as a guarantee for bail; and

- Cash deposit: The accused has a pay an amount of money that they will get back if they appear in court.

It is possible in certain circumstances for detainees to be ‘bailed’ to a supportive organisation, which would act as a guarantor for that person. In this instance, the person on bail would not need to meet any costs, although they would have to comply with the bail conditions.

Example: The Bronx Freedom Fund

The Bronx Freedom Fund is a non-profit, revolving bail fund in New York, USA. The Fund pays people’s bail when they cannot meet it alone, providing immediate relief to those detained, as well as support through the court process. There may be a similar scheme in your jurisdiction.

(iv) Additional requirements to get bail

In some countries, there are additional requirements before bail can be awarded.

Example: South Africa

In South African, the following are requirements to be eligible for bail:

- The accused must have a fixed address that will be checked by an investigating officer; or

- The accused must have assets/money to use as a security for bail.

(c) Bail Conditions

When a judge grants bail to an individual, they may also attach conditions to the bail – depending on the countries. Bail conditions are restrictions on your liberty that you must follow when you are released on bail.

Courts often have a lot of freedom about what bail conditions they can impose. However, in some countries, there is a requirement that bail conditions must be necessary to achieve a certain purpose.

Example: Section 437 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (India)

(3) The Court may impose any condition which the Court considers necessary –

(a) in order to ensure that such person shall attend court; or

(b) in order to ensure that such person shall not commit an offence similar to the offence of which he is accused or of the commission of which he is suspected, or

(c) otherwise in the interests of justice.

Bail conditions are also often imposed so the accused:

- Does not interfere with the investigation (i.e. speak to or intimidate witnesses or tamper with evidence); and

- Makes themselves available if investigators need to interview or ask the suspect questions.

Below are examples of common bail conditions that could be imposed to meet these aims:

- A curfew being placed on the suspect so they cannot leave their house between certain times;

- A requirement that they have to report to a specified police station or bail program at set times;

- No communication with the complainant or alleged victim;

- No communication with any of those people co-accused (i.e. people accused of the same crime);

- Restrictions on movement – not being allowed to go within a specific distance of a specific place, person or persons;

- Having to live at a specific address or with a specific person during the case;

- Having to stay in the country or region and give your passport to the police;

- House arrest. This means you cannot leave your house;

- Not be allowed to have drugs except with a valid prescription.

It is important to check what bail conditions can be given in your country. This may influence your application for bail (see below).

The bail conditions imposed in a case will depend on a number of factors:

- The more serious the crime, the more restrictive the conditions of bail will be and for very severe crimes, such as murder, it is likely that you will not actually be granted bail at all;

- If you have previous convictions, the bail conditions may be stricter next time round;

- If there is evidence that you will try to “flee”, stricter conditions could be imposed;

- If there is a risk you will speak to or threaten a witness (e.g. you know where they live), stricter conditions may be imposed; and

- If you have breached conditions of bail before this will also likely result in tougher conditions being set.

If the conditions of bail are broken, the person can be arrested and charged with failing to comply with their bail conditions. This can have serious consequences. In some countries, this will count as a separate criminal offence that you could be sentenced for. Even if this doesn’t happen, it is likely that your bail will be withdrawn, and you will be held in detention for the rest of your trial.

(d) Bail and the Right to Liberty

If you are not granted bail in breach of the national laws on bail, your detention will not be in accordance with law and will be arbitrary (i.e. a violation of the right to liberty).

Example: Piruzyan v Armenia (European Court of Human Rights)

Mr Piruzyan was held in detention without bail for one year and two months when he was released due to a lack of evidence. Mr P’s detention was not based on a court decision and guarantees under Armenian law had not been followed. For this reason, there was a clear violation of the right to liberty in Art 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Mr P was awarded €8,000 as compensation.

Also, if the laws on bail in your country are very strict or the conditions imposed on bail are very onerous, a detention could be arbitrary even if it is in accordance with the national rules on bail. In this case, the laws on bail could be challenged for violating the right to liberty.

Example: Georgieva v Bulgaria (European Court of Human Rights)

The ECtHR found that there was a violation of the right to liberty when the amount of bail money the accused had to pay was set too high and had not taken into account whether the accused would be able to pay.

How Can I Apply for Bail?

The first place to enforce your right to bail is within the criminal justice process in the case that’s being brought against you. However, there are different ways that an accused can appear for bail in the criminal justice process. The procedure will be specific to your country but below are some common procedures.

(a) When Can I Apply for Bail?

In many countries, you can apply for bail at the police station or at the court, and at any stage of the trial. You may apply for bail orally or in writing.

- Bail can sometimes be granted by police or the prosecutor during the first 24 to 48 hours following your arrest before the accused appears before a judge; and

- Bail will usually be considered the first time an accused person appears before a judge after they have been charged with a criminal offence (this can be called a “bail hearing”).

The specific types of bail and ways to apply for bail depend upon the jurisdiction you are in. You can find some examples below:

Example: South Africa

Types of Bail

- Police bail – You may apply at police station, within 48 hours of arrest. You must make the application before the first court appearance, but this can only be done if you have been arrested for a minor offence.

- Prosecutor bail – The application must be made before first court appearance but to a prosecutor whom has been authorised to grant bail for more serious offences.

- Court bail – This is applied for at the first court appearance or anytime during court proceedings. The Court can grant bail at any time before conviction. The court can impose certain conditions to be adhered to upon someone being released on bail.

Example: Kenya

Types of bail:

- Anticipatory bail: This may be granted to a person before their arrest, provided the person demonstrates that their right to liberty is likely to be violated if they are detained. Persons admitted to anticipatory bail are free from being arrested but are required to report and cooperate with the investigative authorities.

- Bail at the police station: The Police Force Standing Orders require that the officer in charge of a police station releases any person arrested on a minor charge on cash bail. This is a general rule only, and, if the officer has good grounds for believing that the arrested person will not attend court when required to do so, they may refuse bail. Where the accused person breaks bail terms, the police are obliged to cancel the bail, re-arrest the accused person and take him or her to court.

- Bail pending trial: This applies after an accused person is presented before court. If the accused person takes a pleads of ‘not-guilty’, the court releases the accused person on bail pending trial unless the prosecution can show that there are compelling reasons why the accused should not be granted bail, or why certain bail conditions should be imposed.

- Bail pending appeal: This applies after an accused person is found guilty of the charge(s) against him or her after trial and seeks to be released on bail before the hearing of their appeal. It is only granted in exceptional situations. The accused person has to prove that they have a reasonable chance of success in their appeal to be granted bail.

Check when you can apply for bail and what procedure you have to follow in your country.

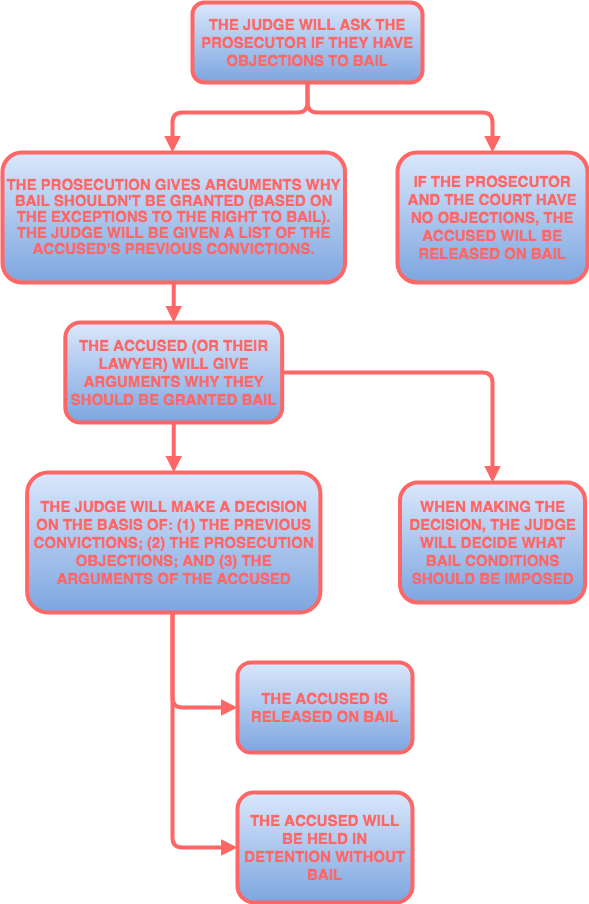

(b) What Happens at a Bail Hearing?

If the decision on bail will be made by a judge, it will usually be made at a “bail hearing” when you first appear at court. The procedure at a bail hearing will change in different countries but it often will look like this:

(c) What Should I Include in My Bail Application?

Prosecutors should oppose bail applications if they have good grounds.

- The prosecutor may argue that an accused person should not be granted bail because they fall in one of the exceptions to the right to bail; and

- The accused/defence lawyer may argue that the accused should be granted bail as none of the exceptions to the right to bail apply in their case.

Where bail applications are made to the police or the prosecutors before a bail hearing, you will be making a similar argument as you will have to persuade the police/prosecutors in your application that a court would grant you bail so they should do so before the bail hearing.

For that reason, it’s important you come prepared with strong arguments if you are making a bail application:

Practical Tip: Making a Strong Bail Application

It is important that your bail application is firmly based on the legal framework that relates to bail in your country. In general, it can strengthen a bail application if:

- You highlight that you have a right to bail;

- You are not accused of a serious crime;

- You have no past convictions or no similar or serious convictions;

- You have a fixed address (i.e. you live in one place and are registered as living there);

- You have family responsibilities;

- You have a job;

- There are people who can act as “sureties” for you (i.e. there are people who can help ensure you obey your bail conditions);

- You can deposit money or a passport as security for bail;

- You have not failed to appear in court in the past;

- The impacts that not getting bail would have on you (e.g. you would lose your home or job, or could not look after your family); and

- You are willing to accept a range of bail conditions.

However, to include these factors in your bail application they must be supported by the facts of your case. For example, you cannot argue that you have a fixed address and a partner if that’s not true.

What Can I Do if I've Been Rejected Bail?

If you or someone in your community is being held or has been held in detention after being denied bail, consider the following steps.

(a) Gather Evidence

If you have been denied bail, examples of useful evidence include:

- Records of your detention: There should be an official record of anyone who is held in a police station or detention facility and the length of time they were held in custody. This should be requested from the relevant police station;

- Records of charge: There should be an official record of your charge, including the time it was communicated to you and the content of the charge (i.e. what crime were you charged with). This should be requested from the relevant police station;

- Court documents: If the judge gave written reasons for denying your bail, it is important you request a copy of these reasons;

- Evidence of your personal circumstances: Evidence that supports the arguments in your bail application (e.g. proof of a fixed address, an employment contract etc); and

- Witness statements: You may need to get statements from witnesses to confirm length of detention and the circumstances surrounding your detention. This could be from a family member or legal representative that knew of the time of your arrest and accompanied you at the time of the charge. For more information on witness statements, see the A4J Witness Statement Guide.

For more tips on how to gather evidence, please refer to How Can I Prove My Case? on the A4J Going to Court: Q&A.

(b) Re-Apply for Bail

In many countries, if you are initially denied bail, you will have another opportunity to apply for bail at your next appearance before the same court. In some countries, this second application can be made on the same basis as the first application. That means it may not be necessary for to bring new evidence or have different arguments, although this may increase your chances of success.

Example: Gama & Another v State of Uttar Pradesh (India)

An Indian court found that the principle of res judicata (i.e. the rule that the same case cannot be heard twice) does not apply to bail application. For that reason, the accused could make a second application to the same court without any new evidence.

(c) Appeal the Bail Decision

In many countries, if you have been refused bail, you can appeal the decision to a higher court. This is different from re-applying as it is an appeal to to a higher court.

Example: Section 65, Criminal Procedure Act (South Africa)

In South Africa, you may appeal a decision to refuse you bail and a bail decision that imposes particularly onerous conditions on you. This must be made on the basis of the same facts as the original application.

For more information on the idea of “court hierarchy” and appeals, see Where Can I Take Legal Action? on the A4J Going to Court: Q&A.

(d) Think about Taking Legal Action

If you have been detained without bail in breach of national law, there will usually be possibilities for you to take legal action against the police or the State outside of the criminal justice process (i.e. in a separate case from the criminal investigation the police are bringing against you).

This legal action could generally be taken in the following scenarios:

(i) You are still detained but, through legal assistance and support, you are able to challenge your continued detention through legal action

Example: Constitutional Rights Project and Civil Liberties Organisation v Nigeria (African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights)

After journalists and activists protesting the annulment of an election in Nigeria, many were arrested and detained without charge and without bail. The ACmmHPR ruled that, among other violations, the detention without the possibility of bail was a grave violation of the right to liberty in Art 6 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. The ACmmHPR continued to order the release of all persons who were still detained from the protests.

(ii) You are no longer detained but want to seek justice and a remedy for your previous arbitrary detention

Example: Buzadji v Moldova (European Court of Human Rights)

A Moldovan businessman was arrested because the police had “reasonable suspicion” he committed fraud. He was denied bail and held in custody for 10 months, before the investigation was ended. This was justified in Moldovan law, which allows people to be held in detention as long as there is a reasonable suspicion they committed a crime (i.e. the same standard as for arrest).

In an important judgment, the ECtHR ruled that:

Although reasonable suspicion of committing a crime was a justification for arrest, it was not a justification for detention after the accused had first appeared before a court (i.e. a few days after arrest).

After this period of time, there must be other concrete reasons to keep someone in detention and deny them bail, such as a risk of committing another crime or a risk they will not appear in court.

The ECtHR found there was a violation of the right to liberty in Art 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights because there was there no assessment of these risks and the accused was simply kept in detention because he had been arrested.

This judgment led to the accused receiving compensation and law reform in Moldova.

The options for legal action will be outlined in How Can I Take Legal Action?