Corruption

Corruption is a problem that has a huge impact on many societies. The A4J Corruption Guide is designed to give you a practical introduction on how to challenge corruption.

What Is Corruption?

Corruption is committing, inciting or facilitating the abuse of public office for private gain. The infographic below can help you identify the different types of corruption, the impacts of corruption, and who it can be committed by.

If you are unsure whether an act of corruption has taken place in your case, consider the following questions:

Focus Point: Identifying Corruption Q&A

1. Are you aware of any abuse of power for private gain in your case?

- If yes, go to the next question

- If no, your case doesn’t involve corruption but you may be able to find other legal solutions on the A4J website

2. What kind of power was abused in your case?

- Physical power? This is not corruption but could amount to another criminal offence

- Power of an employer in an employment relationship – go to next question

- Power entrusted by engagement or contracts – go to next question

- E.g. you make a personal service contract with an agent to sell your car, but the agent’s behaviour damages your interests

- Power in public office? Go to next question

- E.g. a public official such as a police officer asks for money to do their job

3. Did anyone benefit from the abuse of power?

- If yes, go to next question

- It doesn’t matter who profits from the abuse of power

- The beneficiary may be the individual who abused their power or a 3rd party (e.g. a family member or another company). This can still be corruption

- It doesn’t matter when the beneficiary profits from the abuse of power

- The beneficiary may profit immediately or years after the event, but if the advantage gained is still connected to the abuse of power, it is a case of corruption

- If no, your case doesn’t involve corruption but you may be able to find other legal solutions on the A4J website

4. What kind of advantage was gained from the abuse of power?

- Material benefits (money, gifts etc) – go to the next question

- Favours in any form – go to the next question

- Leaked or confidential information – go to next question

5. What was the motive for the abuse of power?

- Material gain – this indicates a corruption case

- Political or ideological motives – this may not be corruption

These are general questions to think about at an early stage. What amounts to corruption for the purpose of reporting or taking legal action will depend on the facts of your case and the relevant law.

We recommend the following resources if you want to find out more about the different types and impacts of corruption:

Key Resource: Transparency International Anti-Corruption Glossary

The Transparency International Anti-Corruption Glossary is an interactive tool that uses animations to explain different types of corruption in a clear and simple way. If you want to get a quick overview of different types of corruption, this could be a good place to start.

Key Resource: The Anti-Corruption Knowledge Hub

The Anti-Corruption Knowledge Hub is an online space where Transparency International presents its research output. It contains a series of topic guides, country-specific research, anti-corruption standards and research papers on different corruption-related issues.

This is a good place to go if you want to deepen your understanding of corruption. You may also be able to find a report or study that could be used in evidence in your case.

Key Resource: The OECD Anti-Corruption and Integrity Hub

The anti-corruption and integrity hub contains studies and papers on corruption issues in relation to different topics and countries. This can be a good place to go if you want to deepen your understanding of corruption in a specific area.

Is Corruption Illegal?

Corruption is not just morally wrong and bad for society, corruption is also an illegal activity.

The following resources could help you find out more about anti-corruption laws in your country:

Key Resource: Legal 500 Q & A Chapters on Bribery and Corruption

On the Legal 500 website you can find Q&A guides that provide an introduction on bribery and anti-corruption laws in 22 different countries. The guides answer questions such as:

- What is the legal framework (legislation/regulations) governing bribery and corruption in your jurisdiction?

- Which authorities have jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute bribery in your jurisdiction?

- What are the civil consequences of bribery in your jurisdiction?

- What are the criminal consequences of bribery in your jurisdiction?

Check if your country is included. This can provide a nice introduction to the anti-corruption laws in your country.

Key Resource: UNODC Database of Legislation

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has an online database of legislation, including anti-corruption laws and case-law from 175 countries.

Use the portal to help find anti-corruption laws in your country.

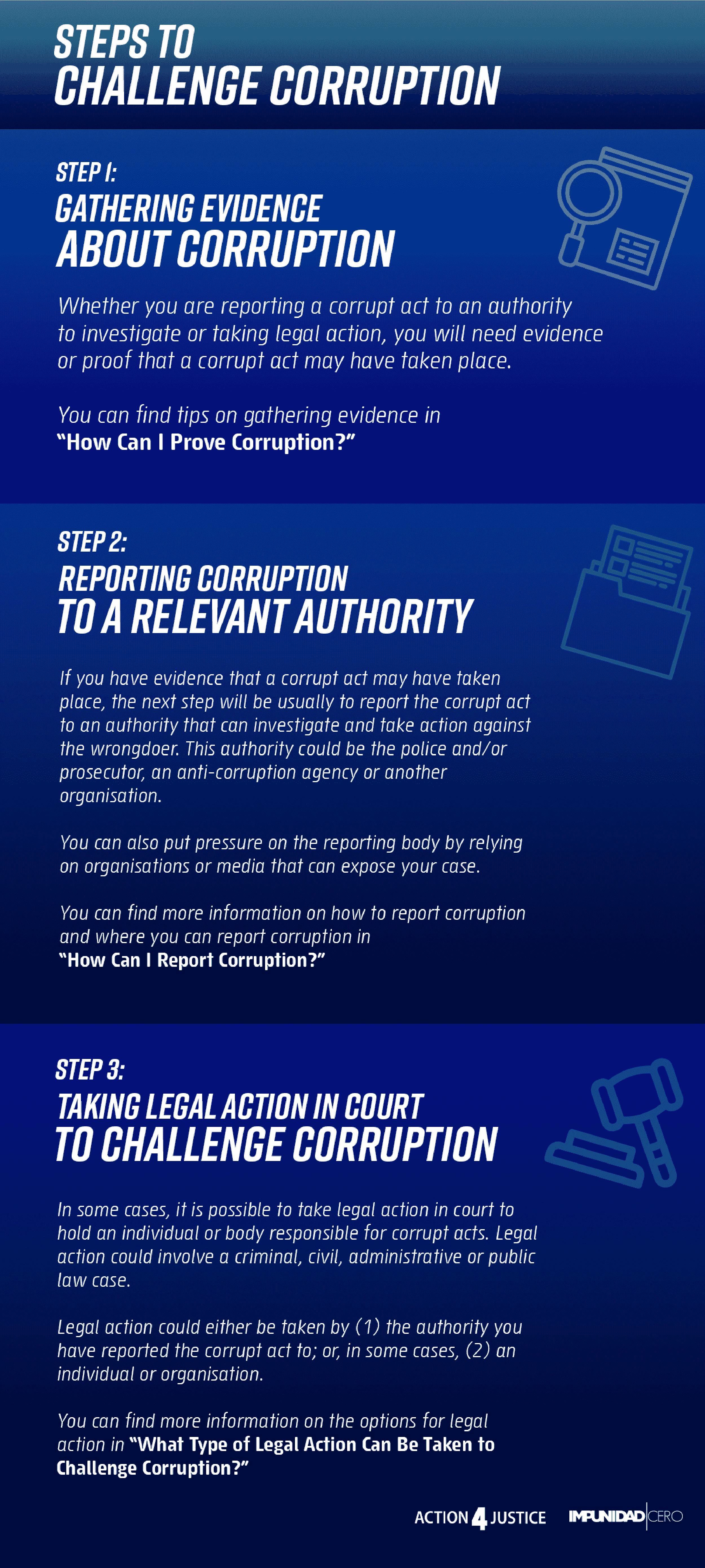

How Can I Challenge Corruption?

Because corruption is often widespread and entrenched in society, it can be difficult to challenge. However, there are steps that individuals and organisations can take to challenge corruption. Some of these steps include:

This Guide will provide guidance on these different steps and help you to think about what action might be right for you.

What Are the Risks in Challenging Corruption?

In a perfect world, all corrupt acts would be challenged. However, reporting corruption can carry on significant risks and costs. It is important to weigh up the risks of challenging corruption with the positive impact that taking action could have before moving forward.

(a) Time and Resources

Challenging corruption can be time-consuming and expensive. The cost and time involved in challenging corruption partly depends on what type of action you are taking to challenge corruption:

- Reporting corruption: The act of reporting corruption should be cost-free. However, it may take time and resources to gather evidence before making a report. Also, consider that you may have to be involved as a witness in the investigation or if the authority decides to take further action.

- Taking legal action: This can be very time-consuming and often costly. In addition to gathering evidence, you will usually need to pay for legal assistance and court fees. For this reason, it’s often best to try and get an authority that you can report corruption to take legal action on your behalf or pro bono lawyers, or get support from a civil organisation in your country providing free legal aid.

The cost and time involved in challenging corruption also partly depends on what type of corruption you are challenging:

- Petty corruption: Challenging individual actions, like bribery of a police officer or public official, is less complicated than challenging grand corruption. This generally requires less evidence, time, expertise and money than challenging grand corruption.

- Grand corruption: Challenging systemic corruption, corrupt government decisions or policies is more complex. This generally requires more evidence, time, support and money than challenging petty corruption.

Because of the time and costs involved, it is key to have support if you’re challenging corruption. For general information on getting support to take legal action, see How Can I Get Support? and How Can I Finance My Action? on the A4J Going to Court Q&A.

Security Risks

There is a risk of retaliation or intimidation by those who have benefited from or are linked to the alleged corrupt activity. Due to the nature of corruption and the people that can be involved in it, there can be high risks for the person who is reporting it.

Depending on the type of corruption you are reporting, security risks could be classified as:

- High security risks: Corruption can involve complex networks between public servants, organized crime and companies. Where organised crime and/or high-level political actors are involved, such as government ministers, there are higher risks. Politicians could use their position of power to threaten or coerce you to stop. Organized crime could use violent tactics to put your life in danger if you’re challenging their interests.

- Low security risks: A police officer or a public official that demands a bribe could prompt them to threaten you with actions such as some jail time or try to intimidate you into making the bribe. However, in general, where you are challenging the corruption of an individual, not a criminal network, the risks are lower.

We strongly recommend you to read the next section to learn what safety measures you can take to reduce the risk of challenging corruption.

How Can I Protect My Security?

Protecting your security is essential if you are reporting or taking legal action to challenge corruption. Any person who reports corruption may need protection. For example:

- Whistleblowers: Persons who report corruption occurring within an organisation;

- Witnesses: Persons who see or hear something related to a corrupt act and can give testimony and/or evidence regarding corruption in a legal case or complaint;

- People or organisations taking cases: Anyone taking legal action to challenge corruption; and

- Journalists reporting corruption.

It is important to have a strategy to protect your security if you are reporting corruption. Before you take a case, it is essential that you:

- Conduct your own risk analysis, outlining the potential threats you may face if you bring a case;

- Plan your security strategy. This could involve identifying government or civil society support mechanisms that could assist you, as well as practical steps to protect your information; and

- Look for support. Identify local and/or international organisations that could give you advice and assistance on your security concerns.

Some specific protection measures are outlined below.

(a) Whistleblower Protection Mechanisms

Whistleblowers are people that attempt to reveal neglect or abuses within the activities of an organisation, government body or company that threaten public interests, its integrity and reputation. Whistleblowers can provide essential evidence about corruption within organisations.

In many countries it is an obligation for public and private entities to guarantee the protection of those who are willing to report corruption, guaranteeing their security and integrity throughout the process. These can be called “whistleblower protection mechanisms”.

Key Resources:

G20 Study on Whistleblower Protection

This report provides a comprehensive overview on the legal frameworks and main features of whistleblower protection in both the public and private sector.

OECD, Commiting to Effective Whistleblower Protection

This document contains an analysis of the whistleblower protection framework in the OECD countries and provides guidelines to achieve effective whistleblower protection in the public and private sector.

In countries with whistleblower protections, there are special protections that aim to alleviate the consequences of any reprisals for seeking to tackle corrupt conducts. Protections include:

- Protecting your information. Whistleblower protection mechanisms often require the data and information of whistleblowers to be kept secret. There can be consequences if the data/information of a whistleblower is leaked;

- Protection against all forms of unfair treatments. Countries with better whistleblower protection laws prohibit all forms of retaliation, disadvantage or discrimination. Violation of these rules give basis to civil or labour law actions.

- Protection against legal actions. Countries with better whistleblower protection laws protect whistleblowers from facing legal consequences for making a disclosure, either because they find themselves accused of charges relating to, for example, libel, professional secrecy or data protection or because they have breached a contractual obligation. Such protection may ential disciplinary and judicial proceedings.

- Interim and injunctive relief. These are legal orders that prevent persons or organisations from doing certain actions, or force them to act in a certain way, while a legal case is ongoing (e.g. this could prevent someone from being fired);Granting legal fees and costs. If a person or organisation is found to interfere or intimidate a witness or person bringing a case, they can be punished at the end of a trial by being forced to pay the other side’s legal costs or an additional penalty;

- Transfer to a new workplace. It may be possible for a court to order a company to transfer an employee to a different workplace within the company where that person is making a complaint and may be at risk in the original workplace;

- Compensation for lost earnings and status, pain and suffering. If an individual has suffered loss by reporting a corrupt activity, they may be entitled to compensation. This could also cover expenses such as medical expenses, relocation costs or protection of identity.

- Personal protection. Many whistleblowers do not qualify for witness protection and it varies from country to country what physical protection whistleblowers and their family members can enjoy.

- Sanctions for retaliation and interference. Some countries allow for civil lawsuits, disciplinary actions and foresee fines for retributions against whistleblowers.

Example: Serbia’s Law on Protection of Whistleblowers

This law protects whistleblowers’ personal data or any data that may be used to discover the identity of the whistleblower, unless he or she agrees to reveal such personal data.

If you are concerned that you may suffer reprisals or other adverse outcomes as a result of bringing attention to the corrupt conduct, check if there are procedures available in your country that may protect you from or compensate you for those risks.

Key Resource: Global Guide on Whistleblower Protection

This guide goes through 16 different countries and identifies the whistleblower protections available in each. For each country, it provides an overview of the legal framework on whistleblower protection, who is eligible and how these protections can be enforced.

(b) Witness Protection

A witness is a person that helps law enforcement authorities to provide evidence and information that leads to identify the person responsible for the corrupt act or who is willing to testify in legal proceedings. This is not limited to people who report corruption within their organisation.

Countries that recognise corruption as a crime need to take appropriate measures to protect witnesses against retaliation or intimidation for their testimony. This protection applies to victims, other witnesses, and it can be extended to family members or persons close to the witness. It is important to mention that a whistleblower may qualify as a witness if they are requested to provide evidence in trial, but whistleblowers will not always qualify for witness protection.

All kinds of measures in each country to protect witnesses should include:

- Physical security procedures, such as relocation and non-disclosure of information about the witness’s identity details and whereabouts in court;

- Evidentiary rules to ensure the witness’s safety during courtroom testimony. This could include allowing them to give their witness testimony in private, out of sight, or through documentary evidence that has their personal details removed.

Example: Hong Kong’s Witness Protection Programme.

The programme is implemented at police stations by the Witness Protection Unit at the Independent Commission against Corruption ICAC to guarantee the protection of persons whose personal safety or well-being may be at risk as a result of them being witnesses.

The legislation first defines the criteria for admission to the programme, provides authorisation to law enforcement authorities to take necessary and reasonable action to protect the safety of witnesses who have been assessed or are being assessed for admission to the programme and establishes, among other measures, penalties for the disclosure of information about the identity and location of a witness who is or has been a participant in the programme or information that may compromise his or her security.

Check if there are witness protection programs in your country that you could apply to.

Key Resource: UNODC’s Country Profiles

In Cycle 1 Reports you can find details on witness protection programs in your country.

(c) Anonymous and Confidential Complaints

If you are going to report corruption, the police, anti-corruption agency or organisation which you report the suspected corruption to may be able to take the complaint forward on your behalf.

In order to protect your identity, there are two possible ways to report corruption:

- Anonymous reporting: This is where the identity of the person reporting corruption is secret from the beginning. Your name and details are not included in the original report, so even the person receiving the report will not know your identity.

- Confidential reporting: In this case, the person receiving the report will know the identity of the person reporting corruption but the identity of the person reporting shall not be disclosed without that individual’s explicit consent.

Example 1: Mexico’s Integral System of Anonymous Complaints (SIDEC)

This mechanism allows any person that has reasonable grounds to prove that a federal public servant or a private entity has been involved in a corrupt act to make a complaint for bribery, influence peddling, abuse of functions or any administrative offence. Through this platform anyone can submit anonymous complaints, videos, photos, documents, witness statements or any other document that can prove the wrongdoer’s corrupt act.

Example 2: I paid a bribe (India, Pakistan, Syria, Nepal and Sri Lanka)

In this platform you can submit an anonymous report if you had to pay a bribe at a government office or you had to say ‘no’ when you were asked for a bribe. In addition, it is not limited to reporting corrupt officials, you can also post if you met honest officers who did their job without asking for a bribe or taking a bribe, and share their story. After you submit your report, I Paid a Bribe reports the incident to media and government officials. Also, if you have a query related to bribery, public services or legal issues you can ask an expert.

(d) Other Practical Tips to Protect Your Security

Other practical steps to protect your security could include:

- Managing your personal information carefully when taking a corruption case. For more information, see How Do I Protect My Information? on the A4J Going to Court: Q & A.

- Changing your email and computer password constantly. This is especially important if you use an online drive or cloud to store documents.

- Consider encrypting your emails. This means they can’t be viewed or understood by persons without permission to read them.

- If you receive suspicious spam text messages or emails with a link, do not open them, this could prevent your information from being hacked.

Whether you are an activist or a journalist, create support networks with your peers if you are covering or investigating corruption.

Find Out More:

We also recommend you to check these websites:

- Surveillance Self-Defense: tips, tools and how-tos for safer online communication.

- Digital Safety Kit: contains guidelines for journalists to protect their accounts, devices, communications, and online activity.

- Digital Security First Aid Kit for Human Rights Defenders: contains different tips to protect the security of human rights defenders, depending on the needs of each person.

- Digital Security Helpline: in case you have an specific query, problem or incident you can contact Access Now

For general information on security issues and legal action, see How do I Deal with Security? on the A4J Going to Court: Q & A.

How Can I Use the A4J Corruption Guide?

This Guide is designed to help you take action to challenge petty and grand corruption. The following sections will provide information to help you answer the following questions:

This Guide is general in scope. It outlines different reporting channels, laws, legal mechanisms and strategies that can be used to combat corruption in different countries. If, after reading this Guide, you are thinking about using legal action to fight corruption, you will need to:

- Research what the national laws and legal systems are in your country; and

- Contact a lawyer or an organisation that can support you when taking legal action.

Contributors

The A4J Anti-Corruption Guide was created in collaboration with Impundidad Cero, a Mexican civil society organisation dedicated to investigating and reporting on impunity and corruption. The Guide was authored by:

- Bianca Bolaños Aparicio – Legal Analyst at Impunidad Cero

- Irene Tello Arista – Executive Director of Impunidad Cero

- Adam Foldes – Anti-Corruption Legal Specialist, Governance Group Member at Action4Justice

- Joshua Jackson – Project Manager at Action4Justice