Divorce

Introduction to Divorce

If you are formally married under the laws of any country, the most common way to end the marriage is by divorce. Almost every country in the world now allows married couples to divorce under some conditions. The exceptions are the Philippines and the Vatican: in these places, a marriage can only be ended by annulment.

Some women face discrimination and difficulties in accessing a divorce. Some countries have different reasons or grounds for divorce for men and for women, making it more difficult for a woman to get a divorce.

Other countries have laws that negatively affect women’s property during marriage or when getting a divorce which may also force women to stay in a marriage. There are also cultural social norms around divorce which may affect the status of a divorced woman negatively.

This section will focus on how to get a divorce and also on different problems that may arise for women from the starting point of accessing a divorce, and how to defend women’s rights through the process of divorce and after.

Reasons or grounds for divorce

Although the divorce procedure is different in every country, there are requirements to get a divorce which are often shared.

Most countries require there to be a cause or a reason that justifies the divorce, called grounds for divorce.

EXAMPLE Zambia requires certain grounds to be met including adultery, unreasonable behaviour, and separation/ time living apart. Similarly, India includes adultery, desertion, insanity, conversion, cruelty, renunciation, presumption of death and venereal disease as grounds for divorce.

The most common grounds for divorce include:

–Disappearance (if one spouse has been absent for a long period of time without contact, usually at least a year or more)

–Cruelty or domestic violence

–Adultery– sexual intercourse with another person.

-Unreasonable behaviour or irretrievable differences that make it impossible to continue living together- This is a broad category and allows you to include many things as reasons, such as infidelity that did not involve sexual intercourse, financial responsibility, etc.

Most countries require the couple to have been separated for a particular amount of time before asking for a divorce. Some countries require separation before divorce for an amount of time and for that separation to include couples living apart. Others, like Chile, allow you to stay cohabitating in the same property as your partner, but declare that you are separated.

You need to know that countries often make a distinction between:

-Distinction between a divorce which is wanted by only one of the two parties (Unilateral divorce) or divorce that is agreed by both parties (mutual consent divorce). Some countries such as Colombia, require that if a divorce is only wanted by one of the parties, then you must wait for a certain amount of time or for certain conditions to happen for divorce to be allowed.

-Distinction between no fault divorces and fault divorces: Countries that allow no fault divorces often require a minimum period of time to take place before asking for a divorce. For example in Mexico– laws differ from state to state, but all have a ‘no-fault’ divorce option, as long as the marriage lasted over one year.

How do I prove my ground for divorce?

If you agree with your partner about getting divorce and the reasons, it is easier as you can have a declaration from each partner on the reasons for divorce.

If you are not in agreement about getting divorced or the grounds for divorce, then you will need stronger evidence.

Grounds such as adultery are often difficult to prove and often require a declaration of infidelity by your partner or otherwise evidence that he is living with someone of the opposite sex, or having a child outside marriage. This is often difficult to prove and people tend to opt for a ground that is easier to prove.

Grounds like cruelty and domestic violence will require evidence such as medical reports, police reports, witness statements, photographs, and copies of for example messages or emails with verbal abuse. If you are in an abusive relationship, you may find advice on finding protection and support under the Violence Against Women guide.

Separation will require you to provide evidence of living apart for the required period of time (6 months, 1 year, or even 5 years in some countries), such as utility bills, change of address, etc. In some countries, couples do not have to physically live away from each other for it to be considered that they no longer share a life together and are separated. This often requires a declaration of separation.

It is important for you to seek legal advice on how to prove grounds for divorce.

How can I obtain a divorce? The divorce process

Although the process may vary in each country, it is often the case that the divorce process is either carried out by an administrative body, such as a Notary or the Civil Registry or that the parties have to go to court.

Divorce through and administrative body:

Where the parties agree to get divorced and are also in agreement about other affairs such as children, property, economic compensation, etc, some countries allow for divorces to take place before an administrative body.

Steps often include:

- Agreeing the terms of your divorce (reasons, what will happen to children, to your family home, to your common property, etc) with your partner. Drafting the agreement and checking that you are happy. You should seek legal advice, independent from your husband to make sure that your rights are being protected properly. For more information on aspects relevant to the terms of a divorce please see Important aspects to be decided when getting a divorce below.

- Take the drafted agreement or form to a notary, a civil registry or other public body. Include your marriage certificate, pay an administrative fee and after a certain time limit, you should be divorced.

- You may need to register your divorce in another public body such as a notary public register, the civil register or other body.

- Overall it should be a brief process.

EXAMPLES: Countries such as Colombia allow for mutual consent divorces to be documented in a joint declaration which is signed before a notary, without having to start court proceedings or pay legal fees and any division of the assets is agreed on a separate document (unless there are children in which Case a Children’s Ombudsman intervenes to see if custody should be decided by a judge).

Similarly, in Nigeria there is a non-judicial divorce and generally, the court will only get involved in this process for administrative assistance or in the case of payment disputes. If this fails, there is a judicial divorce process.

Going to court

Some countries require you to go to court when you are not in agreement over getting a divorce or over other aspects such as which grounds are the basis for the divorce, asset division or custody of children. Other countries require parties to go to court for all cases.

STEPS

- File a petition asking for the dissolution of the marriage. This can be done by one or both parties if they agree.

- The court will check basic requirements are met and send the other party the divorce application. The other party will have to review it and provide their arguments agreeing or not to the divorce.

- If there is agreement you can apply for the court to grant the divorce directly. Some countries may require a court hearing anyway.

- Court proceedings often have a stage of mediation, where the parties are invited to reach an agreement. Parties do not have to agree, in which case the proceedings will continue.

- If there is no agreement there will be a court hearing for a judge to hear the case. This is where show what evidence you have to support not only the grounds for divorce but also other aspects of relevance such as division of the assets, maintenance, etc.

- The judge reaches a decision granting the divorce or not and deciding other aspects.

- There is the possibility to appeal.

Which option is better? You should consult with a lawyer that is independent from your husband, to find out what the best option is for you. Ideally, agreed divorces are faster, but it is still advisable that you get legal advice to see if the terms of your agreement are convenient for you and the steps of your specific divorce proceedings.

Important aspects to think about when getting a divorce

When getting a divorce, you will need to think about what will happen with the custody of common children, visitation rights, maintenance, division of common property and economic compensation.

Custody of children, visitation rights and maintenance for children that will live with you:

If you and your husband have children, the following aspects regarding your children will need to be resolved:

- Child custody or care: who will live with the children in common and have the primary duty to care for them every day. There are several options for divorcing parents:

- joint custody of the children which means that the children will live with both parents, sharing their time between both homes in different proportions.

- sole custody to only one of the parents. This will also mean the other parent should have visitation rights and provide child support to the children.

- Child Support: this is the amount of money that will be paid by the parent that does not have custody of the children to support the children. This is often a fixed monthly amount, although there may be different rules in each country. Countries often regulate a percentage of a parent’s wage that can be destined to child support, but these rules vary in each country.

- Visitation rights or regular contact with the children: this is the time assured to the parent who does not live with the children to visit them. This is often worked out on daily weekly or monthly terms, but it varies in each country. Visitation rights can also be supervised in the event that one of the parents is considered to need supervision for the benefit of the child.

The rules to these aspect will be included in a special law, like South Africa’s Children’s Act, Act 38 of 2005, a Family Code or a Civil Code.

In most systems you can reach an agreement on who will have custody of the children, child support and visitation rights for the other before a notary public or directly before a judge. You should think about what you want and seek legal advice.

If there is no agreement between both parties, a judge will decide. In all cases, the judge will have consideration for the principle of the best interest of the child.

KEY PRINCIPLE UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The best interest of the Child. Article 3 1. States that: In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.

The best interest of the child is applied to each case in particular and will vary in each individual case.

During your divorce proceedings, you will have to provide evidence that supports your requests. This includes:

For custody of children and visitation rights: that you have an adequate place to live, an adequate relationship with your children, economic means to have the children stay with you. Judges should also consider the opinion of children after a certain age. If you are concerned about your children living with your husband you should also provide evidence to support this worry.

For child support: You need to provide evidence about the needs that your children have, such as educational, clothing, food, personal development, health, etc.

The importance of legally deciding these aspects of your parental relationship is that both parties can then enforce these rights legally if they are not complied by either parent.

For example, you can also take the father of your children to court if they do not comply with paying child support or the parent that does not live with the children can legally enforce their right to visit if visitation rights are not respected.

These are changing aspects of your family relationship and can be altered after your divorce to if circumstances change, which will also need to be supported by evidence. You should get legal advice to do this.

Important: If you are concerned about domestic violence in your family, please see our Violence Against Women guide.

Division of the Assets

It is possible that:

-you had property before you married (such as a car, a house or other goods)

-you bought or received property during the time you were married, or

– you did not have any goods or property before your marriage but that you contributed to your household through other means like by taking care of the home and taking care of your children.

In all these situations, you may have property rights that you can claim during your divorce proceedings. This will depend on which rules apply to you.

Most countries have sets of rules on how property is to be distribute if the marriage ends or property regimes that apply to marriage. You should check for each specific set of rules in your country. Each set of rules will have a different effect when you get divorced.

Marital property regimes:

Separation of property:

-Property and income that was bought by you or given to you before getting married and during the marriage remain yours.

-Similarly, all property bought or given to your husband before or during marriage will be his.

– At the time of divorce each spouse retains ownership of all their assets.

-This is beneficial if you have your own property and job income that you want to protect. This is less beneficial if you do not have your own property and contributed to your husband’s chances to buy property in his name only.

Partial community of property:

-Property and income owned before marriage will be owned by the party that bought it or was given it, but any increase in value of the property that took place during the marriage will be joint property and equally divided after divorce.

– Property bought or given after getting married, will be joint property of the couple.

-At the time of divorce, the joint property will be divided equally between you and your husband.

This is beneficial if you do not have your own property and contribute to your husband’s chances to buy property in his name. This is less beneficial if you have your own property and income that you want to protect.

Examples: Cambodia and Ethiopia provide for a partial community of property as the default regime.

Full community of property:

–All property and income from any point before, during or after the marriage are joint property of the couple. If the marriage is dissolved, all joint property is divided equally between the spouses.

-This is beneficial if you do not have your own property and contribute to your husband’s chances to buy property solely in his name. This is less beneficial if you have your own property and income that you want to protect.

Source: World Bank Group, Women, Business, and the Law 2016: Getting to Equal, p. 52, (Washington, D.C., 2015).

In some countries you can know which set of rules apply to you by looking at your marriage certificate and in other countries, this information is held at a Marriages or Civil Register.

In most systems you can reach an agreement on how to divide your assets with your partner before a notary public or directly before a judge. If there is no agreement between both parties, you will need to prove which assets you and your partner have, and a judge will revise this. You should get legal advice to do this.

Economic compensation

It may be that you had to give up employment possibilities whilst you were married. For example, some women stop working to take care of the common children. This can mean that after the divorce, you are in a worse position in your career or to access employment.

When a judge is deciding how to divide the assets between the two parties getting a divorce, in some countries it is possible to ask the judge to provide one of the parties to give the other party economic compensation for the sacrifices you made during the marriage and the impact those had on your income and opportunities.

For example, in Kenya, Section 7 of the Matrimonial Property Act of 2013 says that matrimonial property in divorce proceedings will be split according to the contributions made during the marriage, this includes any childcare given by the mother if she did not work.

In Cambodia, the Civil Code in Articles 972-973 initially states that property is to be divided equally in a 50/50 split between the parties. However, Judges can give compensation or change the division in circumstances like childcare and its effects on earning.

If there is no agreement between both parties, you can ask the judge for compensation and the judge will decide if to give any and how much.

You will need to prove:

- that you had given up your career to take care of children or to take care of the home, or for example that you reduced your hours to take care of your children, and

- that this had a real effect on your career prospects. For example, you left work, or you rejected a promotion. You can do this with emails, witness statements, letters from your employer, etc.

You should get legal advice to do this as in some countries it is more common than others.

Kenya: Nderitu v Nderitu Kariuki [1997] 606 [CAK] Case No. 203 of 1997. Court of Appeal.

In this case, the wife was initially awarded 30% of the matrimonial property in divorce proceedings. The wife argued that she managed two of the family businesses herself bringing the profit to her husband. The judge stated that she did work in the businesses but was weakened by being pregnant and decided that her share should be reduced to 30%. She appealed and the Court of Appeal recognized the important role played by women in childbearing and increased her share to 50% share. The Court of Appeal said that childbirth and struggle faced afterwards should not be a reason for detraction but rather evidence to support a 50% share for the appellant.

Can I get maintenance after the divorce?

Although in most cases the divorce involves a clean break between the parties, there are cases where you can either agree with your partner or have a judge order that you or your ex-partner can get maintenance after divorce.

This happens in cases where one of the parties leaves the marriage with financial difficulties, or where there is a financial imbalance between the two parties.

Bear in mind that:

-Some countries provide for it exceptionally, others more commonly.

-Some countries require you to ask for it during divorce proceedings, others give the judge discretion to decide this.

-If circumstances change, for example if you remarry or if your financial circumstances improve, your ex-partner may ask for the maintenance to stop or be reduced. This will vary in each country.

Rights to Maintenance: South Africa and India

In South Africa, women and men can seek maintenance as an exception. The Divorce Act 70 of 1979 in section 7 allows the court to order spousal maintenance if there was a prenuptial written agreement which included the right to maintenance, or, the court can decide to order some maintenance considering different facts like the economic situation of both parties, earning capacity and economic needs, if there are children, duration of the marriage, etc.

In India, different kinds of marriage allow people to seek maintenance after divorce. If you had a Hindu marriage, you are entitled to maintenance under Section 18 of the Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act (1956). If you had a Muslim marriage, you are entitled to maintenance before you can remarry under the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act (1986) Section 3. If you had a Christian marriage, the court may order maintenance under Section 38 of the Indian Divorce Act (1869). If you had a Parsi marriage, the court may order the one of the parties to pay maintenance if so asked for by the other party under the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act (1936) Section 40. If you had a non-religious marriage, the court can order maintenance for the wife under Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (1973), if the wife can prove that she would be unable to support herself without it and continue living in the common household.

If there is no agreement between both parties, you can ask for it during the divorce proceedings and the judge will decide if to give any and how much. In some countries you can also ask for it after divorce and ask for it to be increased or reduced after divorce too.

Generally, you will need to prove:

- that you are financially struggling

- that you have economic needs to be met, including expenses for taking care of children if there are any

- that you have a prenuptial agreement if there is one.

- the length of your marriage

Bear in mind that the other party may argue that you are financially safe, that you are planning on remarrying or are living with someone else as proof that maintenance should not be given or reduced.

Mohammad Ahmed Khan v Shah Bano (Supreme Court of India) 23 April 1985,

Shah Bano divorced from her husband and she was asked by him to move to a separate residence, after a prolonged period of her living with him and his second wife. They had been married in a Muslim marriage and had five children together. Shah Bano filed a petition in court demanding maintenance from her divorced husband.

Muslim personal law in India only required a man to pay maintenance to his ex-wife for the period of “iddat” (the waiting period a woman must observe after the death of her husband or divorce before she can marry another man), but the Supreme Court of India decided that the religion of the neglected person could not make any difference to the application of secular law and that Section 125 of the Criminal Procedural Code was enacted to provide a quick and summary remedy to a class of persons who are unable to maintain themselves and granted Shah Bano maintenance.

You should get legal advice to do this as the right to maintenance is much more common in some countries and very exceptional in others and specific rules vary.

Customary marriage and divorce

Generally, if your customary or religious marriage is recognised by a registering officer, it should be regulated by the general rules. If your marriage is not recognised, please see our section on customary marriage.

Please bear in mind that there are specific rules about requirements to get a customary or religious marriage and to terminate customary marriage, for which you will have to enquire with lawyers or civil society organisations in your particular country to find out more details.

How to challenge systemic difficulties or disadvantage for women in divorce: Public law or Constitutional challenges

Most countries allow women to request a divorce. For example, in Vietnam, Article 51 of the 2014 Law No. 52/2014/QH13 on Marriage and Family states that men and women can request a divorce. In some places, women are at a disadvantage to start a divorce, or are under more demanding requirements than men to access or start the divorce procedure.

If divorce is easier to access for men than it is for women or if the grounds for divorce are stricter for women or blame women more than men for the same actions, then this can limit your right to access divorce in a way that is discriminatory against women in your country.

Constitutional challenges

Most constitutions include a general provision of equality before the law or non-discrimination. Some countries have constitutional provisions specifically referring to equality in accessing divorce. If the constitution provides for equality between men and women, this should mean that wives are able to divorce your husband in the same way, for the same reasons, same time periods as her husband would divorce her.

For example, article 31 of the Constitution of Uganda states: “…Men and women of the age of eighteen years and above have the right to marry and to found a family and are entitled to equal rights in marriage, during marriage and at its dissolution.”.

The laws of a country relating to divorce may themselves be discriminatory and fail to accord equal status to men and women to seek a divorce. In this case, provisions on equality in a country’s Constitution or other national human rights legislation may be used to challenge such laws. This means that the law that allows or dictates unequal access to divorce can be challenged because it goes against the constitution, or is unconstitutional.

Constitutional claim in a constitutional court. Some countries allow you to go to a civil court.

By whom: the affected person (can be supported by civil society organisations) and some countries allow civil societies to represent the public interest and take a case alone.

Against: restrictive public policy or legislation which makes is difficult for a woman to access divorce or an act by the husband such as retaining money which the wife needs to initiate divorce proceedings. In some countries like in Peru (article 200 of the Constitution), laws are challenged through “unconstitutionality actions”.

Asking for: declare the act, policy or law unconstitutional and have it not applied in your case. In some countries it does not apply to all other similar cases.

How? The process for such a challenge varies between countries – it may be, among other things, called a “constitutional petition”, or “amparo proceedings”.

Steps:

- Finding a person who has had their fundamental rights affected: This would be the wife which is affected by the discriminatory disadvantage or difficulty around divorce.

- Establishing which fundamental rights were affected: the right to equality and/or non-discrimination contained in most constitutions or other national laws can be effective but it could also be that other rights protected by the constitution are affected, such as the right to liberty, right to dignity, access to justice, due process or others.

TIP: Depending on each country, the right to non-discrimination may only apply in relation to the enjoyment of other fundamental rights, rather than as a standalone right.

For example, in the UK, the Human Rights Act requires that discrimination has affected the enjoyment of one or more of the other rights in the Act.

Other countries, like Peru , allow for the right to non-discrimination to be protected as a standalone right.

- Get legal advice on the likelihood of an amparo proceeding for your specific case.

- Initiate legal proceedings showing which rights were affected, how those rights were affected and why it is unconstitutional. You will need to provide evidence.

- The other party, the public authority or the Estate will also get a change to argue and give evidence against your claim.

- If successful, the constitutional courts may provide for an act, law, or policy to be declared unconstitutional. This often means that the act, law, policy cannot be implemented in an individual case (concrete application), but it may in some countries also have the benefit of not being applicable in ANY case (general application).

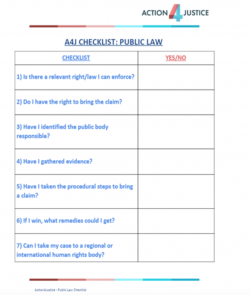

The following checklist may be useful when thinking of a constitutional claim:

Challenging lack of equality for women to access divorce in Case 794-2010 (Constitutional Court), 1 June 2010, Guatemala. General applicationThe Guatemalan Human Rights Ombudsman were not happy that Article 89(3) of the Civil Code of Guatemala allowed men to marry immediately after a divorce, but required women to wait 300 days after a divorce to get married. Following the checklist, they:

- Found a relevant enforceable law which was the constitution of Guatemala, which in its Article 4 refers to the right to equality.

- They also found that they had the right to bring the claim as Article 267 of the Constitution created the constitutional complaint and allowed the Human Rights Ombudsman to bring a claim in Article 134 of the Ley de Amparo, Exhibición Personal y de Constitucionalidad.

- They found the public body or law responsible which was Article 89 (3) of the Civil Code which allowed men to get divorced earlier than women.

- & 5. They gathered evidence and took the procedural steps to make the complaint

- The remedy was that the Court declared the legal provision unconstitutional and not applicable in all divorce cases from then on and ordered the Congress to legislate a new provision which did not discriminate between men and women’s right to marry.

It may be that grounds for divorce are simply different for men than for women in a way that discriminates against women.

Challenging discriminatory grounds for divorce in Uganda :Law Advocacy for Women in Uganda v Attorney General (Constitutional Petitions Nos. 13 /05 /& 05 /06) [2007] UGCC 1 (5 April 2007)

Ugandan NGO “Law and Advocacy for Women” petitioned the constitutional court to strike out laws contained discriminatory rules which made marriage harder for women. Amongst these laws was Section 154 of the Penal Code Act which provided that married men are only liable for the crime of adultery when sexual intercourse takes place with a married woman, while married women are liable for the crime regardless of the marital status of the man.

They made a constitutional petition to the Constitutional Court of Uganda at Kampala against the State asking for Section 154 to be struck out as they considered it was inconsistent with the Constitution, in particular, the violation of the right to property, non-discrimination, equality before the law, prohibition of torture, cruel inhuman and degrading treatment, gender equality and the dignity of women. The court agreed and mentioned international covenants as an inspiration. It declared that the laws challenged, should be stricken out.

In some countries, the division of common property during marriage and when getting a divorce is discriminatory against women which can have serious economic consequences for women that want a divorce, having them often stay in unhappy or violent marriages due to economic need.

Mrs and Mr Gumede entered into a customary marriage in 1968 and had four children. Mrs Gumede was forbidden by her husband to work. Consequently, she was not able to monetarily contribute to the family estate or have any financial independence to rely on when she wanted to get a divorce.

She found that the law was discriminatory, as it stated that the husband had full control of the property and that he was the head of the household and must be obeyed. Mrs Gumede took her case to the High Court first and then to the Constitutional Court, against the South African State arguing that the regulations on customary marriage were discriminatory. The Constitutional Court declared Section 7(1) of the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act (Recognition Act), Section 20 of the KwaZulu Act on the Code of Zulu Law (KwaZulu Act), Section 20 of the Natal Code of Zulu Law (Natal Code) which gave the husband control of all property and Section 22 of the Natal Code which stated that the family owned obedience to the head of the family discriminatory on the grounds of race and gender, making them unconstitutional and invalid in all cases.

The court mentioned international human rights commitments such as the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women in addition to sections 9(3) and 9(5) of the Constitution that expressly deal with equality protection. The result for Mrs Gumede was that she was entitled to the property acquired during her marriage.

It is worth noting that this constitutional invalidity is limited to monogamous marriages, in other words polygynous marriages will still be regulated by customary law for the time being.

A constitutional challenge is often a good route to challenge a law or policy which is systemic and affects more than one individual.

If you are in a hurry to get a divorce, it may be that a constitutional challenge will take too long. It is advisable to seek legal advice to decide whether to meet the existing requirements and go ahead with getting divorced instead.

Regional or international human rights challenges to violations of your right related to divorce

Although there is not a human right to divorce recognised in human right conventions, there are practical aspects surrounding a divorce which can negatively and unfairly affect women.

What are my rights in international law

Article 23(4) of the ICCPR provides that states shall ensure equality of rights and responsibilities of spouses in relation to marriage and its dissolution.

To avoid discrimination, Article 16(1) of CEDAW, calls on States to take measures to eliminate discrimination against women in “all matters relating to marriage and family relations”. This includes divorce.

With regards to property, Article 16.1.h of CEDAW calls on States to ensure “The same rights for both spouses in respect of the ownership, acquisition, management, administration, enjoyment and disposition of property, whether free of charge or for a valuable consideration.”

Article 7 of the Protocol to the African Charter on the Rights of Women in Africa states that States shall enact appropriate legislation to ensure that women and men enjoy the same rights in case of separation, divorce or annulment of marriage, including having the same rights to seek separation, divorce or annulment of a marriage, reciprocal rights and responsibilities towards their children and an equitable sharing of the joint property deriving from the marriage.

TIP 1: You can find a detailed table of international law on marriage here.

TIP 2: You can clickon this link and look for your country on the list. If your country is party to a treaty it must comply with the rights and obligations included in them. Your country may have applied reservations (limitations to the application of the treaty) when they became party to a treaty which you can also read.

TIP 3: You can search for cases in your country or in your regional system and see which rights have been most effective to uphold equality in aspects related to divorce in the past.

How to use these international law provisions in practice?

If your claims and challenges in your national courts are rejected by the highest court, or are not taken seriously, you may be able to take your case to a regional or international body.

These provisions are especially useful for organisations and the community to hold their governments progressively to account particularly towards systemic change.

For more information on how to take your case to an international or regional body, please see the section on this guide “International Mechanisms to protect your rights”.