Public Law Claims and Corruption

Public authorities refer to any body that is in the public sector (i.e. bodies which are part of or controlled by the State). This includes:

Police and law enforcement bodies;

Public service providers, such as public hospitals or schools;

Government departments;

Governmental regulatory and licensing bodies;

Private bodies that exercise any public authority; and

Officials within these bodies.

People deal with public authorities and officials all the time, and decisions of public authorities affect all aspects of public life. Corruption could occur anytime people deal with public authorities or a public official has power to make a decision.

Public law governs the actions of public authorities and officials. This is a broad area of law that includes (1) administrative law, (2) constitutional law, and (3) human rights law.

If a public authority or an official has been involved in corrupt activity, there will likely be a breach of public law. If there is a breach of public law, you may be able to challenge the action or decision of a public authority of the official in one or both of the following ways:

Using an administrative procedure; and/or

Starting a case in an administrative, constitutional or other court.

Is a Public Law Claim Right for Me?

In general, these type of cases have the following advantages and disadvantages:

| ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

|---|---|

| Public law cases have in some cases a lower standard of proof than criminal cases. This can mean that less evidence has to be gathered to bring a successful case, although the evidence still has to be compelling. | Cost. As actions are generally brought by private individuals, in many countries actions can be expensive for the person who is bringing the case. |

| Impact on good governance. Legal action can hold public authorities accountable, providing for better regulation of corruption and good governance in future. Where constitutional or human rights law is involved, it is more probable that a successful case could lead to law reform. | Time and effort. The person bringing the case has to gather evidence throughout the different stages of the administrative and the litigation process. |

| Rapid response. Administrative authorities can react very quickly to prevent impending harms, by issuing interim injunctions before something irreversible happens. | Lack of financial remedies. Financial compensation is rarely available via a challenge in an administrative court or is in lower amounts than in civil claims. |

| Complexity. These cases can be difficult and a lawyer will usually be required. |

What options are available will depend on your country’s legal system and what law is involved.

How Can I Use Administrative Procedures?

In some countries, there are administrative procedures that can be used to challenge the action/decision of a public authority or official before going to court.

(a) Where do I Start an Administrative Challenge?

These are procedures before an administrative body that reviews the actions/decision of a lower level administrative body.

- The reviewing body could be the same body that issued the initial decision and on the applicant’s request reviews its own decisions; or

- It could be a higher level decision-making body, for example a national level environmental protection authority reviews the decisions of its local level office; or

- Sometimes it is a government department with a broad portfolio that can review a lower level administrative decision.

In many countries there are also alternative forms of remedies for maladministration by a public authority/official and these are independent external bodies such as an ombudsman, that can investigate, issue recommendations, statements, engage in mediation, report to the public and to the parliament, but cannot overturn administrative decisions or issue any binding decision.

(b) Administrative Actions Against Public Authorities

In the anti-corruption context, the usual scenario is that there is an administrative decision (or inaction) that may be influenced by corruption and you would like to challenge this administrative decision (or inaction). In some countries, administrative procedures are taken against the public authority that is in charge of the decision or is responsible for the actions of a particular public official.

Example:

A textile factory is granted an environmental permit in questionable circumstances. There are close links between the factory owners and the director of the local environmental agency that grants the permit. The factory then starts letting toxic waste into the river and the local environmental authority does not react for unknown reasons.

Affected citizens can challenge the factory’s environmental permits at the national environmental agency through an administrative procedure. They request an immediate injunction to stop the harmful waste disposal and ask the agency to impose a fine on the factory.

If an administrative authority finds in your favour, it could lead to one of the following outcomes:

- The overturning, amending of a decision from a public authority (e.g. a logging permit is revoked) or restarting the procedure.

- The annulment or cancellation of a public contract (e.g. a contract with a private company to build an infrastructural project is annulled).

- An order, such as an injunction, to prevent an impending harm.

- Imposing an administrative fine on someone infringing your rights.

The administrative authorities’ decisions can be enforced.

(c) Administrative Actions Against Public Officials

In some countries, administrative procedures are taken directly against individual public officials. In these countries, administrative sanctions can be imposed upon public officials through what is called “corporate administrative liability”.

This means that if a public official has been involved in a corrupt activity, this person can be held liable for administrative offenses. For example, if a public servant asks you to pay a petty bribe in order to get public services, an action could be brought against this person.

Example: Mexico’s General Law of Administrative Responsibility

Mexico’s General Law of Administrative Responsibility establishes a legal framework for public servants to follow. This applies to all public officials in the country.

It contains administrative penalties for those public officials who commit “non-serious” (no graves) and “serious” (graves) administrative violations.

- Non-serious violations are those related to the day-to-day activities of public servants and they are generally investigated by internal control bodies (órganos internos de control) within the public entity. These kind of offences include actions and omissions such as refusing to sign a document or not submitting a declaration of assets;

- Serious violations are the ones that are related to acts such as bribery, influence peddling, and fraud. The enforcement body responsible for imposing administrative liability on public servants and private entities in such cases is the Federal Court of Administrative Justice (Tribunal Federal de Justicia Administrativa).

The expected administrative sanctions to both types of violations consist in preclusion from participating in future public offices, economic sanctions, bans for misconduct and dismissal of the public official.

In addition to overturning or cancelling a decision, a successful administrative procedure against a public official could also lead to the following outcomes:

- Dismissal of the public official who was responsible for the corrupt act. Dependending of the offense, this can lead to prohibition to enter into public service for a certain period of time.

- The imposition of a financial penalty for an administrative offence.

(d) How do I Start an Administrative Action?

These are highly specialised procedures. The rules they apply and the process they follow depend on the country’s legal system, the public authority involved, and/or the types of action/decision being challenged.

Practical Tip: Steps for Using Administrative Procedures

1. The first step you need to take is to identify the relevant administrative procedure for the public authority you think has been involved in the corrupt activity (if there is one).

2. Identify the relevant procedural rules you have to follow to make a claim. This could be linked to on the website of the public authority or in your country’s administrative code.

3. Identify the substantive administrative law or regulation you think the corrupt activity has breached.

4. You will generally have to submit a written complaint to the administrative body that will review the complaint. This should outline the facts, your arguments and evidence (for more information see What Evidence do I Need? and How do I Prove Corruption?).

(e) When do I Start an Administrative Action?

In some countries, there is a requirement that you exhaust the remedies in the administrative system before you are allowed to challenge an action/decision in court. This means you must use an administrative procedure before you start an administrative case in court.

- This is particularly common in “continental legal systems”, such as Germany and Hungary.

Use of administrative procedures is often only the first step in challenging the action/decision of a public authority. If you are unsuccessful, it is possible to challenge the decision of the administrative authority in court. This will be discussed below.

How Can I Enforce a Public Law Claim in Court?

Depending on the type of law involved and your country’s legal system, you may have the following options to enforce public law in court:

- After you have used an administrative procedure and the relevant administrative authority has given you a negative decision, the decision of the administrative authority can then be challenged in an administrative court;

- You may be able to challenge the action/decision of a public authority directly in court. Depending on what law is involved, this could be in an administrative court, a constitutional court or another court.

These cases are generally either brought against (1) the administrative authority whose decision you are challenging, or (2) the public authority that made the decision/action in the first place. Where systemic corruption is involved, it may also be possible to bring the claim against a government department or the state as a whole.

(a) What Are the Relevant Laws?

Areas of public law are outlined below that could be used to challenge the corrupt actions and decisions of public authorities. See which most closely relates to your situation. Then check your national law to see what the law is in your country.

(i) Regulations or Legislation Prohibiting Corrupt Activity

There are a variety of specific laws and rules that regulate the activity of public officials and bodies.

- These may be general, applying to all actions of public bodies or officials;

- These may apply to a specific activity undertaken by public bodies or officials (e.g. public procurement laws); or

- These may apply to specific public bodies (e.g. bylaws of public authorities or agencies).

In some countries, actions, policies or omissions of public bodies that are contrary to statutes/regulations can be challenged for being ultra vires or breaching the principle of legality. These actions will be considered unlawful and set aside in a process sometimes called “judicial review”.

(ii) Constitutional Principles and Duties Against Corruption

In many countries, there are general constitutional duties or principles which make an action or omission of a public body unlawful if it is tainted by corruption. In some countries, these principles are expressly outlined in the constitution:

Example: Bill of Rights (Chapter 2 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa)

Article 33 on “Just Administrative Action” states:

1. Everyone has the right to administrative action that is lawful, reasonable and procedurally fair.

2. Everyone whose rights have been adversely affected by administrative action has the right to be given written reasons.

3. National legislation must be enacted to give effect to these rights, and must:

a. Provide for the review of administrative action by a court or, where appropriate, an independent and impartial tribunal;

b. Impose a duty on the state to give effect to the rights in subsections (1) and (2); and

c. Promote an efficient administration.

In other countries, there are generally unwritten principles that can be relied on in court. These duties and principles will often be violated where there’s evidence of petty or grand corruption. For example, decisions of governments and public bodies in some countries can be challenged in judicial review on the basis of procedural unfairness or bias.

(iii) Human and Constitutional Rights

If there is a specific law that prohibits a public body from committing a corrupt act you are complaining about, this will usually be the law you should base your case on. However, human rights or constitutional law could be used to hold the State accountable for corruption in the following situations:

1. Where the State as a whole has not taken enough action to combat corruption in your country.

This could be where the State has not created laws which make corrupt practices illegal, or has not taken action to investigate and punish corrupt activities.

Example: Hugh Glenister v President of the Republic of South Africa

In South Africa, the government decided to abolish an independent anti-corruption body and replace it with a body that wasn’t independent from the government. This was challenged for being unconstitutional. The South African Constitutional ruled that the decision to abolish an independent anti-corruption body undermined the effective investigation into corruption and violated the government’s duty to respect, protect and fulfil human rights in the Constitution.

2. Where widespread corruption of the State has had a clear and direct impact on human rights in your country.

The impact on human rights could be that:

- Corruption in law enforcement agencies can stop them from properly investigating and prosecuting serious crimes, which they are required to do to protect your right to life.

- Corruption within public authorities can divert resources away from schools and hospitals towards the private finances of public officials, impacting people’s right to education and health.

- Corruption in the justice system can prevent people from enjoying their right to a fair trial.

- Or the human rights impact could be that corruption has undermined the democratic or legal system, violating the right to free elections or the right to a fair trial.

Example: SERAP v Nigeria

SERAP, a human rights organisation, brought a case against the Nigerian Government and Nigeria’s Universal Basic Education Commission to The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Court of Justice. A key part of the complaint was that the Universal Basic Education Commission, which was responsible for funding basic education in Nigeria, had mismanaged the national education fund through corrupt practices. This was supported by a report by a national corruption watchdog.

The Court ruled that the corrupt practices of the Commission had led to less money being invested in education and the government had not taken enough steps to recover or compensate the lost funding to education, and that this violated the right to education protected in the African Charter of Human and Peoples’ Rights. As a remedy, the court ordered the State to provide funds to cover the shortfall in education funding caused by corruption.

Example: Legal and Human Rights Centre and Others v Attorney General (Tanzania)

In Tanzania, a civil society organisation challenged an electoral law that allowed political candidates to give gifts to voters (“takrima”). This was challenged because it facilitated corruption, leading candidates to start buying votes.

The Tanzanian High Court found that the electoral law violated the rights to equal treatment and non-discrimination regarding political participation in the Tanzanian Constitution as they discriminated against political candidates with lower incomes. They also found that the electoral law violated the right to free and fair elections in the constitution by undermining the democratic process.

There will often be more direct ways to challenge corruption by public authorities, but it may be worth including human rights arguments as an additional ground to argue a public authority’s actions have been unlawful.

(b) What Procedure do I Need to Follow?

How to bring a public law case before a court varies in each country.

- In civil law countries, there are often administrative courts specialized in receiving administrative cases to challenge an action/decision of an authority which are ruled by specific administrative laws.

- In common law countries, there is often a process called judicial review where a court hears public law claims directly without the need for using an out-of-court administrative procedure.

- In some countries, there are specialised constitutional courts that hear cases involving constitutional law, and other courts (e.g. administrative courts) deal with different matters of public law.

Focus Point: Amparo Proceedings

In many Latin American countries, the amparo trial (or tutela) is one of the most effective ways to defend oneself from corrupt government acts when constitutional rights are violated.

- The amparo trial can be invoked by any person to whom his or her rights have been violated.

- Amparo trial and its procedural venue can vary according to the procedural law of each country.

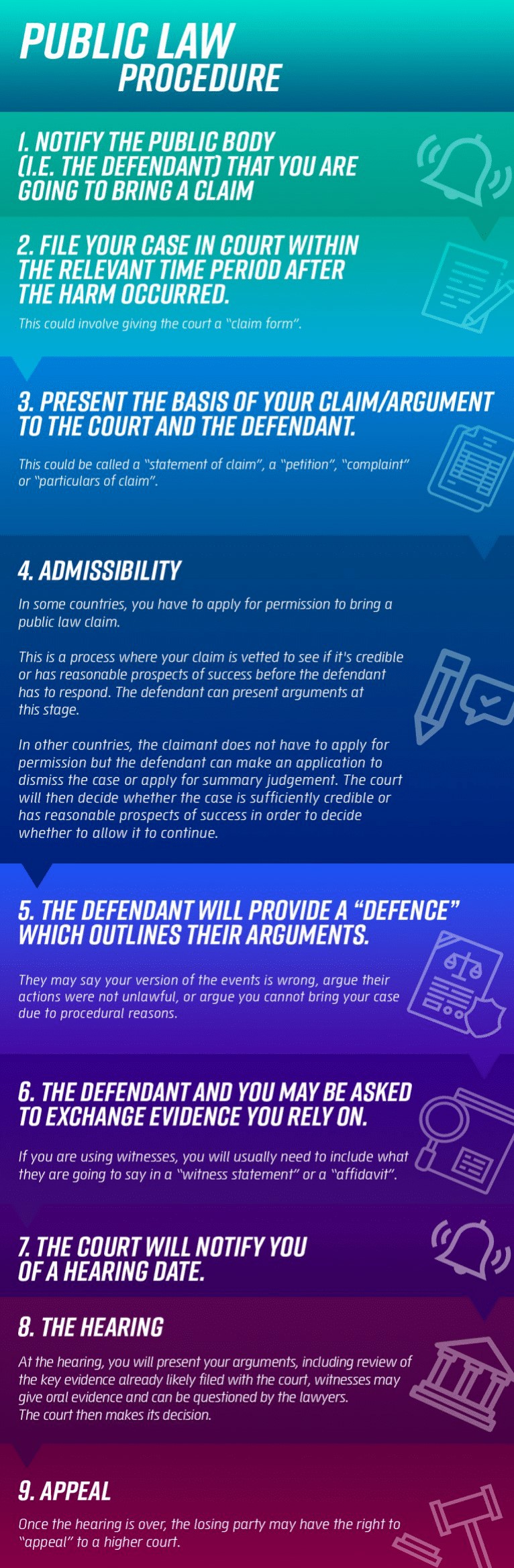

Remember, in some countries you must first exhaust relevant administrative non-judicial procedures before starting an administrative public law case in court. However, once you are able to bring a case to court, the procedure often follows the general steps below:

The above steps most accurately reflect the judicial review process in common law countries. Civil law countries will often have different steps, but some of the steps above will still apply.

(c) What Happens if I Win?

A successful case in an administrative or constitutional court could potentially lead to one of the following options:

- Remedy by achieving the annulment or amendment of the original administrative decision.

- The overturning, amending of a decision from a public authority (e.g. a logging permit is revoked) or restarting the procedure.

- The annulment or cancellation of a public contract (e.g. a contract with a private company to build an infrastructural project is annulled).

- Court order for the government or public authority to take action to combat corruption.

- Law reform. In some countries, courts have ordered the government to pass new laws or change existing ones.

Who Can Bring Public Law Claims in Administrative Procedures or in Court?

The person bringing a claim is often called the “claimant”, “plaintiff” or “petitioner”.

The person bringing the case (and his or her lawyers) are responsible for:

- Gathering evidence to support your claim. In some countries, administrative authorities can assist in this process (e.g. the ombudsman).

- Conducting the legal analysis (i.e. make the argument that the conduct of the defendant has violated the relevant law). Their legal analysis has to be supported by the evidence they have gathered.

- Going through the various procedural steps required to start an administrative procedure and to take it to court.

The following groups can often bring administrative cases:

(a) Individuals Affected by Corruption

Actions under public/administrative law are generally brought by the individual on whose interests an administrative decision (tainted by corruption) has an impact.

Example: Hugh Glenister v President of the Republic of South Africa

This case (see above) was taken directly to the South African Constitution Court by a concerned citizen. He did not have to show he was personally impacted by corruption as it was an issue of public interest.

Also, in many countries, groups of people who have been affected by an action or inaction of public authority can bring a case together. This is often called a “class action” and can help spread the costs of bringing a court case.

(b) Civil Society Organisations & Public Interest Groups

In some countries, claims can be brought by NGOs and civil society organisations with an interest in challenging corruption. Often NGOs active in other fields such as anti-discrimination, environmental protection, consumer rights have the procedural rights to represent diffuse groups (where each individual affected cannot be identified) and bring an actio popularis before administrative bodies and courts. By challenging the administrative decision under the law of a particular sector often the harms resulting from corrupt acts can be remedied too.

For more information on organisations that could help you, see Where Can I Find More Information and Support?

(c) Anti-Corruption Agencies and State Prosecutors

In other countries, anti-corruption agencies and state prosecutors can bring actions under public, administrative, civil and human rights law.

Example: Brazilian Prosecution Service

The Brazilian prosecution service is independent of the government under the Brazilian constitution and has the power to bring civil, administrative and constitutional cases to defend public interests of society as a whole, of particular groups and individuals. This includes taking cases to challenge corruption in public authorities.

What Evidence do I Need?

In public law cases, the claimant or petitioner has the “burden of proof”. In many countries, you have to prove your case to a standard of proof known as the balance of probabilities (i.e. there is more than a 50% chance what you are saying happened).

(a) What do I Need to Prove?

In administrative cases, you will generally need evidence to:

- Identify the decision or the action made by the public agency. For example, the licensing of a project and the related corrupt act;

- If you are challenging a licensing decision of a public body, information on public licences are normally held by the public office charged with oversight. Sometimes, public offices have to publish license information. This information can be found on public websites, or annual reports of the public office or can be obtained through information requests either by interested parties or under the provisions of the right to information law if there is one in your country;

- Identify the public agency and the public officer within it that committed the acts you are complaining of. It may also be helpful to find out the membership of any collective body responsible for the decisions, and the extent of that body or committee’s decision-making power;

- Demonstrate how the act violated a particular law or lower level regulation and why it has to be annulled or amended;

- Demonstrate the events which took place. For example, if payments were made, you will need to provide as much information as you can about the amount of the payments, when they were made, and payment methods, such as bank transaction or cash payment. If other property was given or taken as a result of the corrupt acts, you will need to provide evidence of this, including (if possible) the current location of the property;

- Demonstrate the corrupt nature of the decisions or acts; and

- The consequences of those decisions or acts.

It will be necessary for you to obtain detailed and precise information on each of these points, so that the court can understand the situation fully.

Practical Tip:

You may also be able to compare one decision of a public body with other similar decisions which were taken apparently without corrupt motives. This could help you show that the decision you are seeking to challenge may have been motivated by improper considerations such as corrupt payments.

Finally, if you find that you do not have all the evidence of corruption in relation to the original decision, you may nonetheless be able to pursue an administrative appeal or challenge if you can show that the decision was based on irrational or improper grounds, or that it was reached by following an inappropriate procedure.

For more information on gathering evidence of corruption, see How Can I Prove Corruption?